The sunshine that makes you feel joy when it drifts in through the window on a winter day can be the same light source that triggers intense pain in a migraine sufferer who does their best to hide from it.

How can light have such strong and differing effects on us?

It might come as a surprise that scientists don’t really know. Yet.

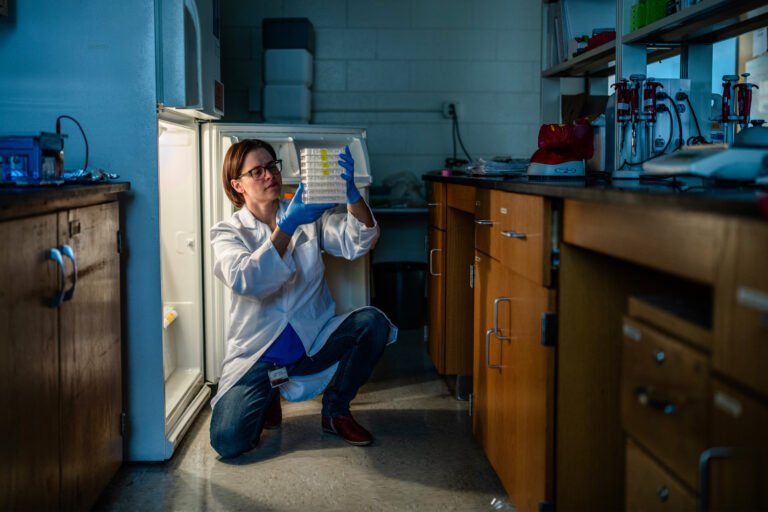

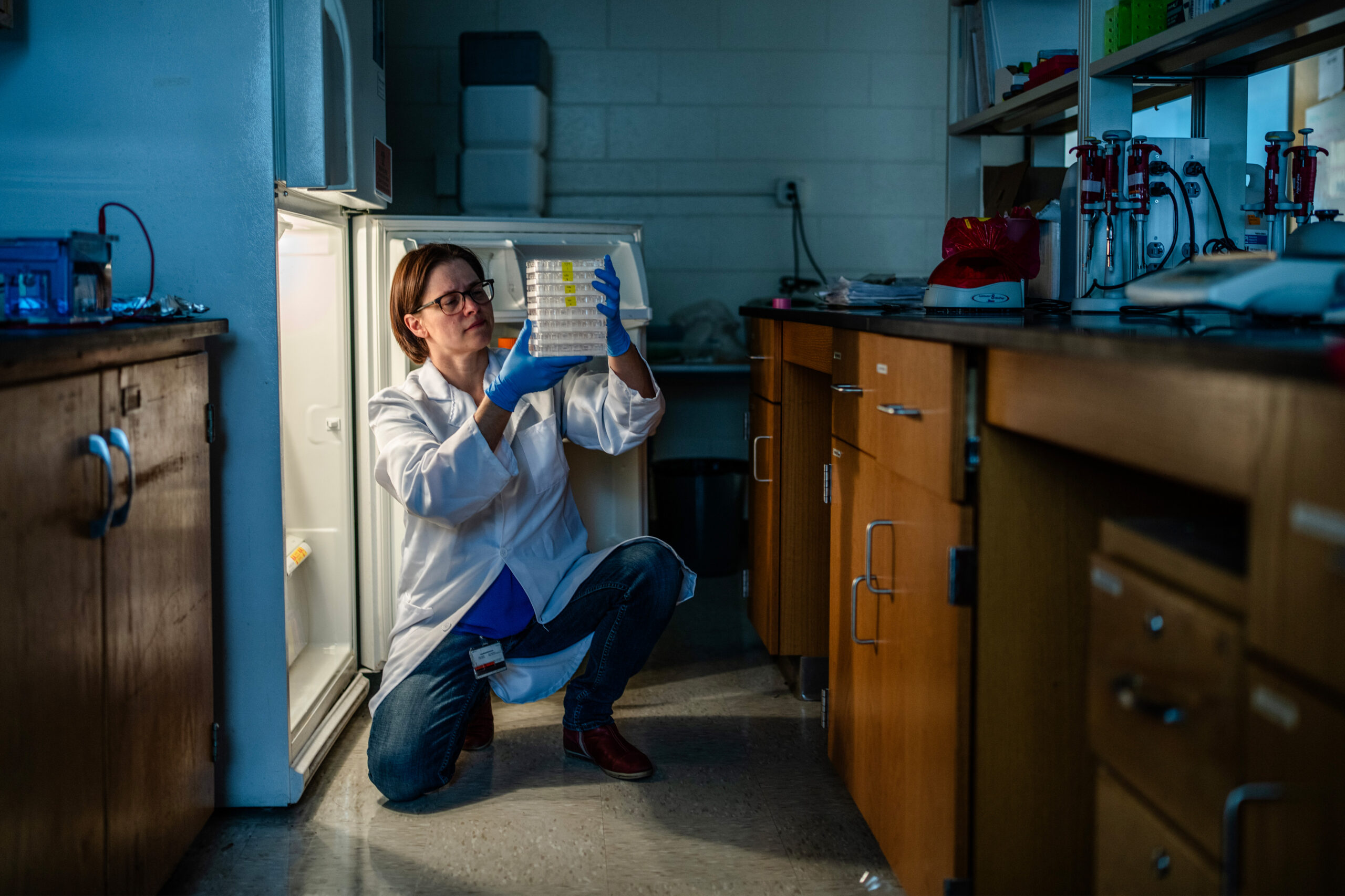

“We’re at the tip of the iceberg,” says Dr. Deanna Arble, an associate professor of biological sciences at Marquette and a trained circadian biologist specializing in the science of circadian rhythms, sleep, obesity and diabetes. Hers is the only lab in the nation seeking to identify how environmental light impacts breathing. Awarded a five-year $1.25 million grant from the National Science Foundation, Arble has merited this CAREER funding — the most prestigious grant the NSF awards to early career faculty — to map out how light travels through the body and affects our breathing and respiratory processes.

Beyond this ambitious project, Arble is a true teacher-scholar enabling her undergraduate and graduate students to partake in critical research in their academic journeys — and she is hell-bent on furthering scientific discovery through interactive and bold means, including exploratory art exhibitions at the Haggerty Museum of Art.

With humble confidence, Arble notes that the CAREER project will help the scientific community address an important knowledge gap by identifying the neural pathways — the circuitry — that light information follows from the retina to the brain to signal respiratory processes.

Science will gain a much-needed road map.

“We already know light directly affects our mood, like in people with seasonal affective disorder,” she explains. “Light improves our alertness and our focus. It makes some people sneeze, and others have light-induced migraines. All of that is connected and shows how important it is to learn how light travels through the body to affect biological processes, like breathing.”

The science that makes us

Breathing frequency is a key part of the puzzle. Historically, scientists have focused on metabolism as the driver of these rate changes. That’s likely not the complete picture. Following studies published in the early 2000s, scientists learned there are natural peaks and valleys in our breathing throughout the day and that these are measurable — there is a discernable 24-hour pattern.

With most of the field still focused on metabolism as the primary modulator of breathing, Arble is navigating how each system (metabolism, circadian clock and breathing) interacts with the others. She hypothesizes that light plays a major unifying role.

Arble is interested in testing and understanding two mechanisms: One is the pathway light takes to indirectly influence breathing — essentially, how light affects the body clock. This path likely has slow but strong effects on breathing by transmitting fluctuations in activity, sleep and metabolism.

The second is the less explored pathway light takes to directly influence breathing by stimulating other parts of the brain — neurons in the mid-brain region.

A light-polluted world — and potential consequences

The linking of daily breathing fluctuations to light also opens up new questions. How do disruptions in the light cycle, such as too much light at night, affect breathing-related health problems?

Researchers have found that 80% of the world’s population is subject to increased disease risk, including Alzheimer’s, through exposure to artificial light at night. Receiving blue light at the wrong time of the day causes circadian disruption, which in turn could exacerbate disease. As part of the CAREER project, Arble is measuring the depth of breathing when a sudden light burst at night disrupts mice. Such occurrences are suspected of inducing shallow breathing and could lead to the discovery of other adverse effects. Scientists have already correlated light and breathing trouble in respiratory diseases including sleep apnea, asthma and obstructive lung disease; all are linked to circadian rhythms because of their episodic nature.

“Blue light is especially good at activating the cells in our eyes that talk to our brain’s internal clock, but it also sends signals to a number of other brain regions in ways we don’t yet understand,” she says.

Living in an overexposed light environment — think bright street and yard lights shining into bedrooms, night-lights built into room outlets, and ever-present phones, computer and TV screens — has left many of us receiving light signals too early in the day and too late into the night. This concerns scientists. “Light at the wrong time can lead to unexpected signaling from those cells. Conversely, light during waking hours, especially in the morning, is really important to regulate our body clock,” Arble explains.

Of mice and measurement

Better understanding of breathing suppression from interruptive light at night has the potential to inform and improve patient care. “Individuals with sleep apnea, for instance, exhibit more apneic events when sleeping in well-lit rooms. What about other respiratory diseases?” she asks. “What are the consequences of putting someone who’s already pathologically pushed towards breathing depression into an overnight hospital room that has all the lights on at all times of day? It is a sobering thought.” For certain patient populations with respiratory concerns, this scientific knowledge at its best could help avoid potentially fatal episodes where light exposure in care settings increases respiratory distress.

Arble’s research will in turn inform more specific studies on light intensity and wavelengths. Because our eyes are especially sensitive to blue wavelengths, this information could lead to changes in the lightbulbs we use at night, for example, to allow society to continue to function without adversely affecting breathing.

A true teacher-scholar

Sophia Halick, a sophomore and MU4Gold scholar, has worked closely with Dr. Deanna Arble and other lab associates on many projects.

“My senior year of high school, I applied to 14 colleges. It was because of Dr. Arble that I chose Marquette at all,” she says. Because Halick wants to become a professional researcher, the undergraduate opportunity in the Arble lab has been career-forming for her. “Our conversations have been the primary way I’ve learned about the world of research. I’m not sure how to put into words the value of these conversations for me. I trust her to give me the best advice for my personal journey. She’s incredibly savvy,” says Halick.

“Deanna has this remarkable ability to guide others with her clear vision and enthusiasm,” echoes Dr. Martin St. Maurice, fellow biologist, collaborator and department chair.

Recent psychology graduate Ellie Thorstenson, Arts ’25, adds that Arble’s mentorship has poised her to become the best psychiatric physician she can be as she pursues med school. “She taught me the importance of scientific communication — how to write abstracts, present at conferences and engage with other researchers. I’m listed as a co-author on a manuscript we recently submitted for peer review.”

“Working with her was an exceptional experience. It’s because of her that I know research will remain an important part of my future as a physician,” Thorstenson says.

Determined to flip the script

During almost nine years at Marquette, Arble has churned out steady progress on her specialties: the effect of light on breathing, the effect of obesity on breathing, and the relationship between sleep and breathing. Her research projects have been constant and overlapping, and the discipline required to sustain that pace is impressive.

“She’s had so many momentous and interesting things happen,” says Dr. Michelle Mynlieff, Arble’s colleague. “She is a great story in the making.”

With three current projects supported by the NSF and the National Institutes of Health (including one as co-investigator to improve independent breathing following spinal cord injury) and eight more conducted by undergraduate and graduate students with her oversight, balance has been key.

Arble sees poking at the status quo as central to her approach to scientific study, pushing back against the assumption that metabolism is a prime driver of breathing rates and that light is an afterthought. So, a key part of her CAREER grant aims to help students see that science requires a commitment to inquisitiveness and risk-taking. Arble pushes her students to discard their perfectionism, saying: “It’s a huge problem in science. Students aren’t practiced at troubleshooting or thinking on their feet. We work a lot on developing a new mentality.”

Arble and Lynne Shumow, curator for academic engagement at the Haggerty, have collaborated to offer science majors formal training in divergent thinking through a creative problem-solving course. Both the course and its complementary art exhibit bring artists and scientists together to model creativity and teach tools to encourage more of it in scientific research design.

“The course and the exhibit act as a bridge to solving real-world problems. I feel very strongly about that. This is not just problem-solving for scientific research,” Arble says.

“This is something that every undergrad can do. You don’t have to apply it to biology; you can apply this creativity and critical thinking to anything you set your mind to,” she explains.

“That’s the beauty of research.”