Borsuk’s essay and all colleague reactions are available at this link.

Alan Borsuk has taken on the daunting task of judging decades of school reform in the United States. The vast majority of reform, he concludes, hasn’t helped students, or the nation, very much. The core problem, Borsuk concludes, is that policymakers “from presidents . . . to local school boards” have “overreach[ed],” telling schools and the people in them what to do rather than leave educating to educators. But there’s reason to view the arc of school reform from a different, more optimistic perspective.

Remember, half a century ago, public education was largely a black box. Policymakers and taxpayers had few ways to know whether students were learning or if their educational investments were paying off. Title IX hadn’t transformed the educational landscape for women. Black and Latino students were largely excluded from the nation’s education equation. And while the pandemic has been devastating to the nation’s students and educators, a silver lining has emerged in the form of a nascent movement to bring high-quality tutoring—once the preserve of families who purchased it privately—into public schools.

Today, thanks to the bipartisan interventions of federal and state officials and many other people, public charter schools are providing high-quality education to millions of students. Transparency has become a watchword in education. While only half of white students and 25 percent of Black students earned high school diplomas in 1950, it’s expected today that nearly every student be taught to high standards through high school. There’s far more equity in education funding than in the past.

Importantly, the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the federal government’s respected measure of student achievement, reported steady gains in reading and math from 1994 to 2012, the height of the national commitment to higher school standards. Gains were greatest among Black and Latino students.

Here’s the reason why state and federal leaders became increasingly involved in school policy, why they became the engine of reform and reform became increasingly top-down: The leaders of the nation’s 13,300 school districts and 100,000 schools largely failed to respond when tasked, in the wake of the civil rights movement and the changing nature of work, to do more for more students.

It’s a function of the nation’s decentralized public education governance system that 49 million public school students must depend on the inclinations of local school leadership. From the George H. W. Bush administration through the Barack Obama administration, successive Republican and Democratic presidents put increasing pressure on those local school leaders to raise student achievement through mandates for tougher standards, more testing, and greater accountability.

Are we where we want to be in public education? No. There was a tremendous amount of lost learning during the pandemic. Standards dropped. Student absenteeism spiked. College readiness declined. More broadly, education quality continues to be too closely correlated to students’ skin color and parental income, and the bipartisanship that fueled reform for several decades has vanished, with Republicans now focused on diverting public money to private schooling and Democrats, beholden to teacher unions and other public education protectionists, offering little by way of school improvement strategies.

Of course, teachers, principals, and local administrators are key players in school improvement. If they aren’t bought into reform strategies, the chances of success are greatly diminished, as was the case under the federal No Child Left Behind Act. But to expect reform to originate independently in thousands of local school districts (nearly half the nation’s districts have fewer than 1,000 students) is more than unrealistic. As public education’s past makes clear, millions of students suffer when local schools are left to their own devices.

Illustrations by Robert Neubecker

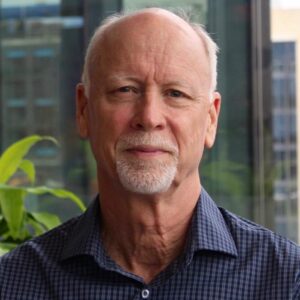

Thomas Toch is the founding director of FutureEd, an independent think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. Toch helped launch Education Week and is the author of two books on American education, In the Name of Excellence and High Schools on a Human Scale.