Death was part of the job for Dr. Madeline Wake. She had seen a lot of it in her extensive career as a nurse. Her husband, James, had not seen death in his social work career. So, when they comforted a family friend as she passed away from cancer, it was the first time that he’d ever seen someone die.

“He asked me what we do when someone dies in a hospital and I told him we take a moment to sit there with them,” Madeline says.

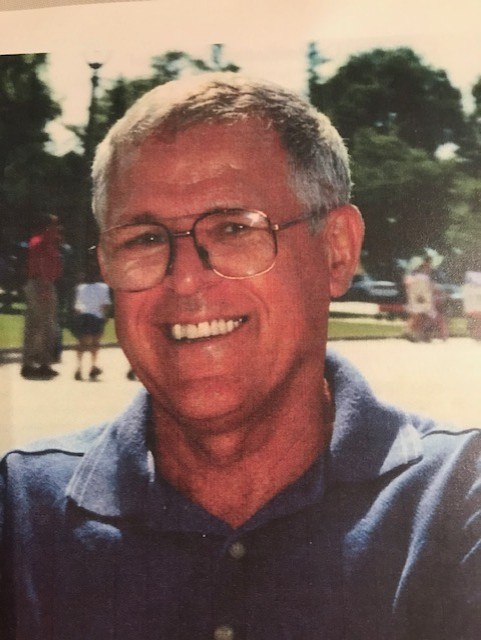

James took that lesson to heart by becoming a hospital chaplain, a role in which he comforted hundreds of terminally ill patients and their families before his own death from brain cancer in 2004. Madeline, dean emerita of the College of Nursing and former Marquette provost, wanted to do something to honor the sort of life her husband lived. She applied memorial contributions to establish the James Wake Memorial Lecture.

“We wanted to establish this platform to hear from national leaders in end-of-life care and get acknowledged experts on the subjects of dying and bereavement in front of our university audience,” Madeline says. “The ultimate outcome we want to see is improvement in care for both the dying and the bereaved.”

“The James Wake Lecture reflects so many of the values we hold dear in the College of Nursing: holistic healing, advocacy for the vulnerable and respect for all people,” says Dr. Jill Guttormson, dean of the College of Nursing.

The Institute for Palliative and End-of-Life Care began sponsoring the lecture under the leadership of Dr. Sarah Wilson soon after James’ death. Dr. Susan Breakwell continued the tradition, securing nationally recognized palliative care researchers, educators and practitioners as keynote speakers. Hundreds of audience members attend in-person and virtually each year.

For Breakwell, a home care nurse and an experienced palliative care champion, the subject resonates deeply.

“In many ways, palliative care is the heart of nursing,” Breakwell says. “It encompasses so much of what nursing is all about: care for the whole person. It’s not just their physical care, it’s their body, mind and spirit.”

A Prayer From James Wake

“I have learned through chaplaincy to honor the spiritual journey of each person as it unfolds, moment by moment, breath by breath, heartbeat by heartbeat.

Each person’s journey is valid. Each moment of the journey is sacred.

You are a person of goodness. Unconditionally loved by God. I honor your journey. I honor you.” – James Wake

Care for people at the end of their lives often crosses boundaries from the medical to the spiritual. Madeline recalls a time where her husband was providing chaplain services to someone whose religious beliefs called for members of his community to be near as he died. The hospital room could not accommodate the crowd without disrupting patient care. James arranged for a conference room near the patient for the community.

That act of consideration was a comfort in the patient’s final hours.

End-of-life care practitioners also see people who do not know what they want at the end of their lives. Often, it takes a life-threatening situation for a close friend or family member to make people think about how to spend their final days. Wake and Breakwell hope people do it sooner.

“We’ve brought representatives from the Law School at times to advise people on advanced directives,” Madeline says.

“There are plenty of people who have spoken or written to us after the lecture to thank us, saying that the lecture has inspired them to establish or update their end-of-life care wishes, advance directives or living wills,” Breakwell says. “Even some students have told us they’ve done it.”

The Wake Lecture also provides a forum for people to talk honestly about their own mortality, an exercise that is equal parts necessary and uncomfortable.

“You’re talking about an emotionally laden issue and it’s so difficult because people’s upbringings, cultures and religions vary so much on how end-of-life care is treated,” Breakwell says. “But it’s so important to confront any barriers to having an honest conversation about this because you only get one shot at the end of your life. There’s a lot we can do better, and we need the patient’s partnership for things to improve.”

Madeline counts the lectures she attended as among her most treasured memories of a 34-year career at Marquette. That career included teaching hundreds of classes, providing continuing education for practicing nurses, presiding over the nursing school as dean for a whole decade and helping create positive change as provost. However, this lecture is personal for her in a way that transcends almost everything else.

“Jim always said that the only two professions where you get paid for loving are social worker and ministry, and he got to do both of them,” Madeline says. “I’m so glad we get to honor his spirit on a regular basis like this.”

For more information about this year’s Wake Lecture on Friday, Nov. 8, visit our website.