Economics professor Dr. Ethan Schmick digs into vast records of the Grange to explore farmer collaboration as an underappreciated force in American agricultural history.

American farming history contains a riddle.

“The U.S. population has increased, the farming population has declined dramatically, and yet farms are more productive than ever,” says assistant economics professor Dr. Ethan Schmick, whose research focuses on collective action, Black–white inequality, and economic history.

Scholars tend to credit mechanical and biological innovations for the boom, but Schmick thinks they’re overlooking an important factor: farmer collaboration. His new research project investigates the influence of a national farming organization known as the Grange.

“There have been big changes in agriculture,” Schmick says. “Perhaps one piece of the puzzle is farmers being able to better share ideas.”

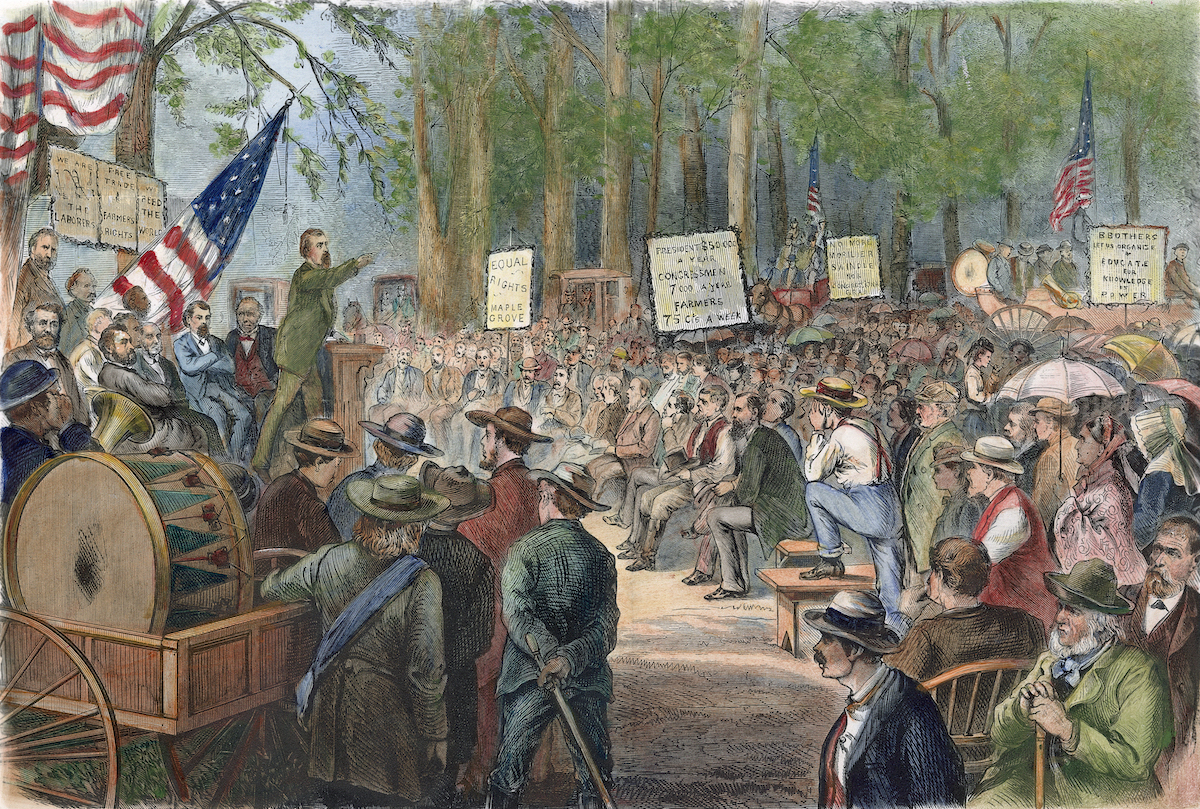

After the Civil War, Minnesota farmer and U.S. Bureau of Agriculture clerk Oliver Kelley toured struggling farms in the American South. He envisioned an organization to share best farming practices and advocate for favorable legislation. In 1867, he and six agency colleagues started the National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry.

“Farmers would come together and form a local branch of a Grange,” Schmick explains. “There were also county Granges, state Granges and the National Grange.”

At the peak, 40,000 communities spread across almost every state had a branch of the Grange. Members discussed matters like crop varieties, pests and fertilizers.

Initially the Grange had secret handshakes and passwords aimed at protecting members’ economic interests, often from railroad agents that were charging astronomically high costs for transporting agricultural products. Unusually for the time, women and Black people could become Grangers.

At the peak, 40,000 communities spread across almost every state had a branch of the Grange. Members discussed matters like crop varieties, pests and fertilizers. Schmick wants to see whether this cooperation made a significant difference on agricultural yields.

The Grange intersects with his research into economic ripples from agricultural pests like the boll weevil, an infamous cotton-consuming beetle that entered the U.S. in 1892. Protecting crops was a costly effort involving burning stalks after harvest and tilling the burned material. All that work was wasted if neighboring farmers didn’t do the same. “Combating the boll weevil and agricultural pests in general required a community effort,” Schmick says.

Schmick is tracking which communities formed Granges and will then perform statistical analysis to see how successful they were agriculturally relative to places without branches.

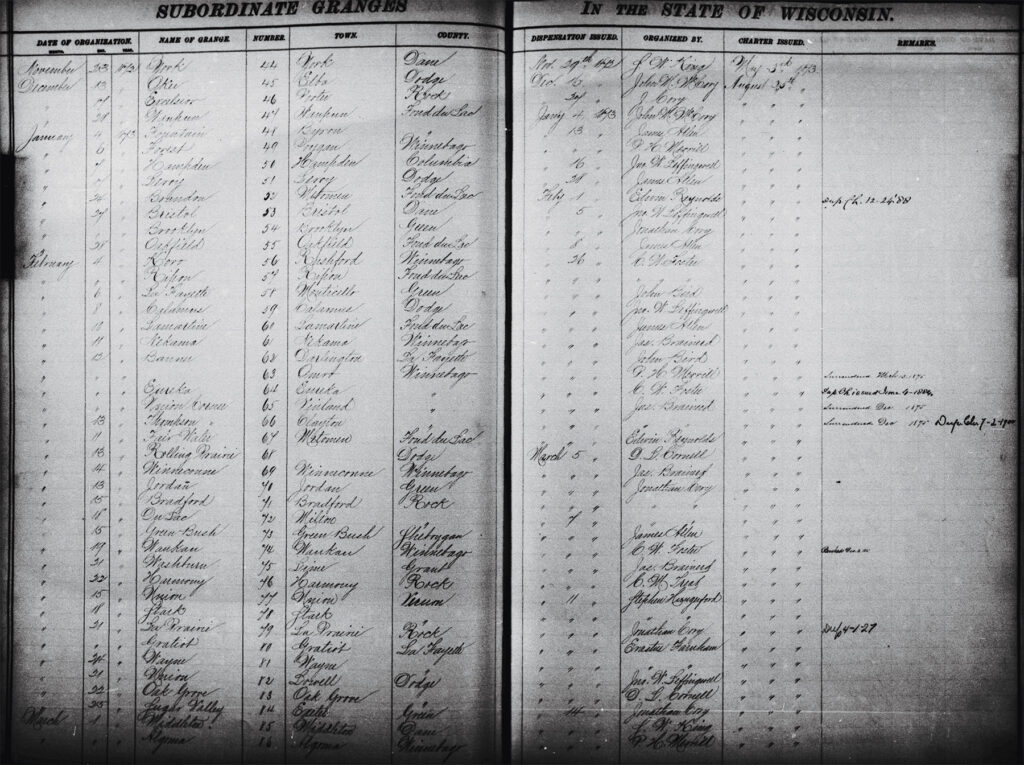

When he reached out to the National Grange organization, which still exists, staff provided archival records. The only hitch: They’re entirely handwritten. Alabama’s state list, for example, includes pages of entries in ornate script starting with the state’s first Grange, formed in 1872 in Yorkville. Extending to include each local organization established through the 1950s, Alabama’s list alone stretches 40 pages. “There are 1,000 pages of this,” Schmick says of the entire collection.

Schmick is getting the pages professionally transcribed with support from a $5,000 Economic History Association grant award. With the data in a spreadsheet, he can start his analysis.

Another key data source is already in a usable format. The U.S. Agricultural Census collects information from every farm on crop type, acres grown and acres harvested. Schmick also anticipates help this summer from a Marquette undergraduate transcribing the Wisconsin Grange records and performing initial analysis on them.

His research is still in the early stages, but Schmick expects to find that the Grange mattered economically, which has potential implications for modern-day farmers. Perhaps adopting some of the Grange’s tenets about cooperation could increase farm productivity and profitability in low-income regions, he says. “I certainly think there are insights for today.”