By Karen Coates

“Taliban is everywhere … .”

It’s Aug. 13 in Milwaukee, Aug. 14 in Kabul, two days before the Afghan capital will fall to the Taliban, roughly two weeks before the U.S. will complete its withdrawal from its last post at Kabul’s international airport. Tensions flare.

Seven thousand miles away, at Marquette, Patrick Kennelly, Arts ’07, Grad ’13, follows the news on his phone and fears for his friend. He sends a message:

“In these difficult times how can we help you?”

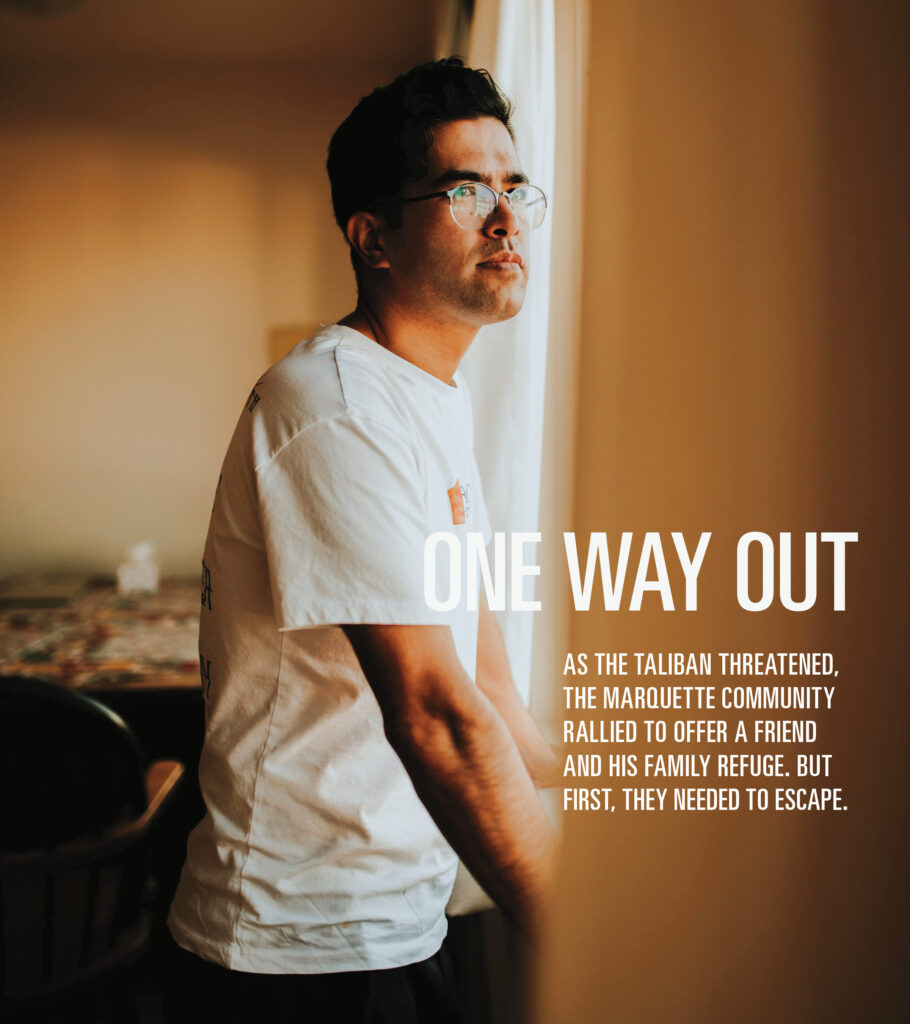

The friend is Basir Bita: a colleague, an activist, a target. Bita’s 17-year-old daughter, Mahdia, was injured in a drive-by shooting. His wife, Hosnia Rezaee, worries the Taliban will kill him. This danger stems from Bita’s work fighting for the rights of the marginalized: women, minorities, the poor and LGBTQ members of Afghan society.

It’s a mission Bita shares with Kennelly, a thread binding Afghanistan and Marquette. The two have worked for years with partners to build a program in nonviolence connecting Bita’s cohort of young peace workers in Afghanistan and Marquette’s Center for Peacemaking, which Kennelly directs. But now, plans perish in the rubble of bombs and guns. Dreams take a rear seat to immediate needs.

The drama unfolds over Facebook and WhatsApp, long-distance lifelines of hope. Within hours, Kabul falls. The airport remains a rare escape option, per a U.S.-Taliban deal to cooperate in the massive, frenzied evacuation that marks the end of this 20-year occupation.

“What are you going to do? Can you get a flight?” Kennelly asks.

“It’s difficult now. All flights are booked for all neighboring countries … ,” Basir replies.

“Sending love to you and yours.”

“Likewise. Love you all.”

A week later, the airport is a maelstrom. More than 800 Afghans cram into a U.S. Air Force cargo jet heading for Qatar. Others cling to the outside of the aircraft. Videos go viral, the world watching as the plane lifts and bodies drop from the sky. Bita and his family try to flee seven times.

“I witnessed … literally thousands of people storming into the airport,” he recalls. “Every time.” U.S. soldiers try to curb the chaos, cursing and pointing guns at desperate faces. By now, the Taliban form an intimidating force around the airport. Soldiers haunt the nightmares of Bita’s son, Barbod. “You can imagine how horrible it is for a 5-year-old kid to go through all those challenges,” Bita says.

Half a world away, Kennelly and his colleagues mobilize. The center issues a statement asking friends and supporters to pray for an end to the suffering, to help in any way they can. The appeal ignites action. Activists, peacemakers, educators, administrators — so many want to help. Someone asks, can Marquette provide education to an Afghan in need? A donor pledges to fund a scholarship.

Kennelly calls Rana Altenburg, Bus Ad ’88, associate vice president for public affairs. Will Marquette get behind this impromptu idea? She advises checking with her boss, Paul Jones, vice president for university relations. It’s 7 or 8 p.m. when Kennelly calls, and Jones is at Valley Fields watching a Marquette men’s soccer match since his son plays on the team. As soon as he hears the story, Jones says yes, let’s find a prospective student.

After more than a dozen years of collaboration, the Marquette center and its partners had a list of 90 or so Afghans needing aid — and they had to choose one. A sobering triage hinged on the question: Where could the greatest good be done? “And Basir rose to the top,” Kennelly says. Not only did he have stellar academic credentials and a longtime desire to further his education, but an F-1 student visa could bring his family of four to safety.

Kennelly makes a call on WhatsApp: “Hey Basir, it’s Pat. Give me a call on Signal. I have a couple of options I wanna talk to you about.”

Marquette had a plan for Bita’s future. But first, Bita had to get out of Kabul.

Basir Bita didn’t know he was Afghan until he was 13 or 14. Born and raised in Iran, he thought of himself as Iranian until one day, a school official insulted him with a slur he paraphrases as, “You stupid Afghan!”

“I’m not an Afghan!” he replied in shock.

“Yes, you are,” the official said. “Go home and ask your parents.”

So he did, and they told him: “We are originally Afghans. And we should be proud of our identity.”

That was Bita’s introduction to racism. It shook and shaped him. His family was Hazara, an Afghan ethnic minority, and had fled to Iran. “We were all refugees, even though I was born there.”

The episode opened his eyes to the bigotry embedded in Iranian society and left him with a desire to figure out who he was. He read history, studied the culture and surrounded himself with other Afghans in Iran.

Jump ahead several years to 2003. Bita was taking Iran’s Konkour, the brutally competitive nationwide exam used to assign spaces in public universities. He finished in the top 1,000, out of more than a million. Good enough for him to enroll in the second-highest-rated public university. But soon, the university told him refugees were ineligible for admission. Even more galling: Syrian and Iraqi refugees gained admission, he says, but “they refused to accept any Afghans.”

The incident redirected Bita’s life. “When I was rejected, I decided to go to Afghanistan and pursue my education.” It became a place for him to further develop his identity and connect with his roots. From the day he started preparing for his move, he thought, “This is home. … This is where I belong.” Remembering those days, he always smiles “because they were nice days,” he says.

But they didn’t last. Although he’d grown up speaking Dari, one of two official languages in Afghanistan, he was required to learn Pashto — the other language — for a class. “It was difficult,” he says. His grade suffered because of the language barrier, and he saw his experience as another form of discrimination, paralleling an ethnocentrism soon revealed all around him — across the university, in the social, political and economic layers of the country as a whole. For Bita, this was an entrée to activism. He and friends joined Hazaras student associations, “so we had our own network; we were doing our own advocacy,” he says. “I had to struggle and fight for my rights, even in my own country.”

One of eight such academic centers at Jesuit institutions worldwide, the Marquette Center for Peacemaking was founded in 2008 to cultivate the next generation of nonviolent peacemakers, “young people who would have the courage to challenge injustice and address social realities,” Kennelly says.

His role guiding the center grew from a connection with peace activist and Nobel nominee Kathy Kelly, who served as peacemaker-in-residence at Marquette during the center’s inaugural year. Her mission, rooted in resistance to war, spans from Haiti to Bosnia, Iraq to the West Bank. She’s served prison time for planting corn on nuclear missile silo sites and been fined for taking medicines and toys to Iraq in violation of sanctions.

Kelly invited Kennelly — then a Marquette grad teaching history in the Milwaukee Public Schools — to volunteer for a project documenting stories of displaced Iraqis in Syria and Jordan. This work, Voices for Creative Nonviolence, earned international recognition and prompted appeals from young Afghan activists. “We’re a small but nascent peace group trying to explore the power of nonviolence,” they wrote. “Will you come visit our work and help connect us?” Thus began the relationship between Bita’s group and international peacemakers.

By 2011, when Kennelly made the first of many trips to Afghanistan, he was the Marquette center’s associate director and driven by a noble ambition: ending the war. “It is clear that the use of violence is impotent in its ability to resolve this conflict or bring peace,” he wrote at the time. Only through person-to-person relationships could peace prevail.

Kennelly recalls wearing Western clothes, walking through parks and drinking tea. But the sense of danger escalated, particularly as President Barack Obama oversaw a drawdown of U.S. troops from 2011 to 2016. “We started wearing more traditional clothes and changing our route,” Kennelly says. It proved safer to avoid hotels and stay in private homes. “People would roll out a mat and just sleep on the floor,” he says. They shared family meals, sitting on cushions, eating traditional Afghan bread. With Bita as their adviser, the Afghan activists took their cues from the likes of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and Pashtun pacifist Abdul Ghaffar Khan. They built a peace park promoting love in the face of war. They taught women to sew duvets and sell them for a profit. They ran a program for street kids, offering compensation in food for school attendance. They brought people of different ethnicities together in communal space to learn how to live in peace.

These were examples of “positive peace,” which scholars differentiate from peace’s more common form — basically, the absence of war. Positive peace is something deeper, “about building systems and structures where everyone’s needs are met, human rights are respected,” explains Chris Jeske, Bus Ad ’11, Center for Peacemaking associate director. It is the ideal to which Bita has always aspired.

Kennelly describes 36-year-old Bita as “a quiet guy … always reading and wanting to talk about big ideas.” Starting around 2017, the two worked with a small team in Afghanistan to co-teach an introductory course for college-age Afghans on nonviolence theory and practice.

Kennelly wanted to get to the heart of a key question: What does nonviolence mean in Afghanistan, where most of his students had never lived without war? “The number one thing that stood out to me is that it wasn’t theoretical at all for these guys,” Kennelly says of the students he encountered in person and online. In one conversation, Americans pledged nonviolence, even if under threat. Then an Afghan student spoke: “I, of course, want nonviolence, and everything, but if somebody came through the door with a gun or was trying to kidnap me … I don’t know what I’d do.” He spoke not of textbook dogma but a visceral understanding of fear.

It was an eye-opener for Kennelly. “There was more of an honesty in thinking through what it would actually mean to be nonviolent.”

Three months before the U.S. pullout, the Taliban mount an offensive, seizing territory victory by victory. The dangers in Kabul intensify. Bita and his family start moving from house to house, lying low

to evade capture. “My biggest concern in Kabul was that if the Taliban arrested my husband, they would definitely behead him,” Rezaee says, Bita translating.

Bita has had many jobs — in research, translation, education and leadership — for scholars, agencies and foundations. He has worldwide friends and partners. “When something inhuman happens in any part of the world,” he says, “I feel I am responsible for that because they are my sisters and brothers.” His profile as a peacemaker makes him a known figure to the Taliban. “It was incredibly difficult,” Rezaee says. “Getting to a safe place was my only hope.”

One night, Bita is driving his family home from a party when five gunmen try to force them off the road. “We have no idea who the people were,” he recalls. When he fails to stop, the gunmen open fire. Mahdia is hit in the foot. After shrapnel is removed at a hospital, she is shaken but survives. They all survive on the flimsy line between endurance and despair.

It’s late August, the final hours of the U.S. evacuation from Kabul’s airport. There is no longer a way out by air from here. Instead, Bita and his family travel overland 260 miles northwest to Mazar-i-Sharif. The Taliban control almost all aspects of life and society now, but there is talk of an evacuation flight leaving from there.

Along the road, Taliban soldiers search Bita’s bus. When they reach him, they demand: What’s inside your bag? He is terrified. His laptop holds all his data, his life and identity. This single moment could ruin his family’s future. It’s food for my kids, Bita says. And to his great relief, the soldier tells him, “OK.” The family makes it, intact.

“Just arrived in Mazar-i-Sharif,” Bita texts Kennelly on Aug. 30. But they’re not safe. The next day, Taliban soldiers fire shots in the air to celebrate their triumph. There’s a curfew for civilians. “If Taliban find you on the streets they will stop you, they will do a body search,” Bita shares in a WhatsApp message. “They will ah look up at your cell phone and if they found any connections, who knows about the consequences.”

Bita later sends a photo of the famous Blue Mosque in Mazar-i-Sharif, where children scamper about with colorful balloons. This tranquil spot, surrounded by hundreds of white doves, is often called an “oasis of peace.” Within days, a Canadian nonprofit group with ties to Bita arranges tickets for the family on a humanitarian flight to Islamabad in neighboring Pakistan. It is “the very last flight of the United Nations for Afghans,” Bita says. “There were no more flights of such kind in the future.”

But even their passage to Pakistan does not end this long, circuitous search for sanctuary. The family essentially hides in a hotel, venturing out only occasionally, inconspicuously, for fear of being seen by Taliban supporters. It is the ubiquitous fear of any refugee who knows their oppressors have eyes in many places. Someone always knows something.

Finally, after 47 more days, comes a time of grace. The family — Basir, Hosnia, Mahdia and Barbod — catch a flight to Canada, landing in Toronto last fall.

Now safely in Canada and with U.S. visas anticipated, Basir, his wife, Hosnia, and their children, Mahdia (17) and Barbod (5), expect to be in Milwaukee by summer. Photography by Dylaina Gollub.

“I keep telling myself, ‘Everything is going to be all right soon,’” says Rezaee, who still struggles to grasp this new life and its semblance of security. “Sometimes when I talk about what I went through in detail, I feel chopped, and tears come down my face.”

As the journey of Bita and his family winds slowly, hopefully toward Milwaukee, Kennelly and colleagues raise roughly $110,000 for the family. It’s $40,000 short of their overall goal, Kennelly says, but there is still time to donate.

Through the collaboration of a department head, dean and donors, Bita is prepared to enroll in Marquette’s Clinical Mental Health Counseling master’s program this fall. Others are working to help Mahdia pursue her studies, since she was just shy of high school graduation in Kabul. And Notre Dame School of Milwaukee, led by Patrick Landry, Arts ’08, will welcome Barbod for first grade.

Meanwhile, Bita keeps working to help others stuck in Afghanistan. He sends immigration information to friends, fueling their flagging stamina. “They have no hope for their future,” he admits.

He counters pain with fortitude. His decision to study counseling at Marquette is driven by the needs of his people. His transition to academics, prompted by the cruelty of conflict, may ultimately pave his future path toward peace. “I am hopeful that someday I will be able to establish my own nonviolence institute in Afghanistan,” he says. “I was very close … before the fall of Kabul.”

Until then, he has new chapters of his story to write. He and his family are in Vancouver now, as they pursue U.S. residency. In summer — if expected visas come through, and circumstance throws no more curveballs their way — the family will move to Milwaukee. Until they find a place of their own, Kennelly and his wife, Emmey Malloy, Arts ’06, Grad ’12, will shelter them in the spacious house they share with their two children and her parents. There is room for more, Malloy says, in both house and heart.

“Dear Patrick, How are you, Emmey and little buddies?” Bita asks in a recent message. “We learn new things about Canada every day. Nice place, but chilly. … You must remember that I have been writing the story of my journey from Kabul. … It’s more than 55,000 words now. … The purpose of writing the story is to raise awareness and advocate for those still stuck in Afghanistan but in dire need of support. …”

“Congrats on the progress,” Kennelly replies.

“Thanks. The work is not finished yet.”