Dr. Dora Clayton-Jones was wrapping up a Bible study with her friends when the host happened to turn the television to a local news channel; a reporter was live at the scene of an apartment fire, the building engulfed in flames. Clayton-Jones and her friends talked about how badly they felt for the people who lived there; people whose belongings were undoubtedly lost. Then, the reporter read the building’s address.

“I realized that it was my address and my apartment,” Clayton-Jones says.

Now a professor in the Marquette College of Nursing, Clayton-Jones counts herself as lucky. Lucky to have not been asleep in that complex, which was her original plan for the day. Lucky to have graduated college after losing almost everything she owned. Lucky to have deviated from her original career path and chosen nursing, which bonded her to the profession that raised her up after tragedy.

“There was no way I could have come back to school that semester without the support of the nursing community,” Clayton-Jones says.

It’s a community that Clayton-Jones almost never joined. Her original plan when attending UW-Madison was to enroll in the pre-physical therapy program with ambitions of being a physical therapist. However, after shadowing at a PT clinic, she concluded that the career wasn’t what she was looking for and pivoted to nursing.

Clayton-Jones already had some experience working around nurses; she volunteered in a local hospital near her home in high school. While there, Clayton-Jones discovered the intense levels of care and concern nurses gave to their patients, which eventually convinced her to join the profession.

“That experience at the community hospital really left an impression on me,” Clayton-Jones says. “I helped at the information desk and got to volunteer on the pediatric unit, where I spent time doing activities with children. Playing games with them, reading to them and sitting with them when nobody was there was the first time I realized this is something I was really passionate about.”

That passion sustained Clayton-Jones to the cusp of graduation. She was in her final semester when, on a day like any other, she came back to her apartment tired after a long day of classes.

“I was working on a paper and studying for exams at the time,” Clayton-Jones says. “I had eaten lunch and I remember being exhausted. It felt like I’d done as much as I could do for the day, and everything was organized enough for the next day to where I felt good enough to take a nap.

Then I got a call from a friend who said she was going to attend a Bible study and she asked me if I wanted to go. I told her that I was tired and wanted to take a nap, but maybe next time. As I was about to lie down, something just hit me to say, ‘you know what, go to the Bible study, you can sleep later.’ So, I decided to go.

“If I had lied down, I probably would not have woken up in time to get out.”

By the time she got back to the apartment, it was nearly burned to the ground due to defective wiring in the building. Clayton-Jones’ possessions were lost, including everything she needed to graduate. The notes she’d spent years accumulating, study materials for upcoming exams, costly textbooks, a term paper nearly completed — all ash among the building’s charred remains.

Almost instantly, Clayton-Jones’ nursing support system snapped into action. College administrators allowed her to take incomplete grades on her classes, preserving her GPA. Professors collected money for her without anyone asking them to do so; enough for her to get back on her feet. Friends helped with nearly everything the donations wouldn’t cover.

“The national Black Nurses Association, the college nursing student body and staff, the people who were nurses at my clinical sites; they all gave kitchen items, bathroom items, cash, everything. By the time I got all these donations, I had everything I needed to start over,” she recalls.

“All the professors put the word out that they needed to support this student who was a senior and having a difficult time. I was able to graduate because of them. The same level of service they showed me, I wanted to bring to my professional life.”

It took another full year and a few months of staying with a friend before Clayton-Jones finally graduated, walking across the stage on a chilly, rainy day, filled with inner warmth after accomplishing something she’d almost abandoned.

“I think about my mother who wanted to become a nurse and wasn’t able to do that for a variety of reasons; it felt like I was representing her and so many other people that may have been deterred by something in their past,” Clayton-Jones says.

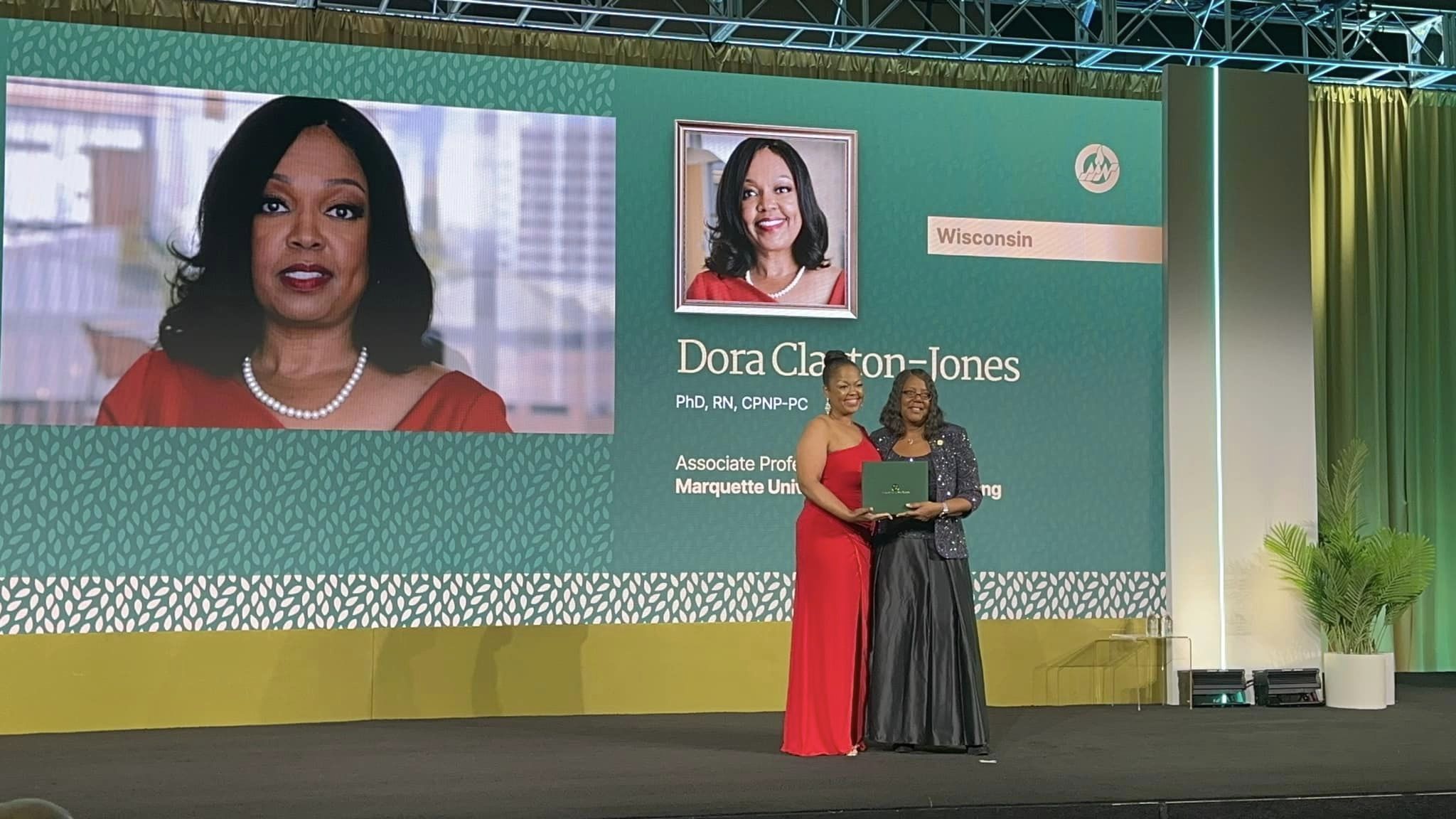

Out of tragedy sprung a nursing career that spans more than three decades and a teaching career at five different colleges. Clayton-Jones has been a pediatric nurse, a preceptor and a prolific researcher, specializing in improving care and quality of life for patients suffering from sickle cell disease. She received the 2023 Vel R. Phillips Trailblazer Award from the Milwaukee Common Council in March for her extensive contributions to the profession and was recently inducted into the American Academy of Nursing.

However, the what of Clayton-Jones’ career isn’t as important to her as the how. Clayton-Jones believes in meeting challenges with courage and empathy, an ethic ingrained into her in the months after the apartment fire.

“That time in my life made me more empathetic to the needs and concerns of students,” Clayton-Jones says. “You can come to the profession with a passion for wanting to help and support people, but I think once you’ve gone through certain challenges and experiences, you can’t help having that feeling deepen and have even more compassion. I’ve learned how to have more of a listening ear and pause and try to discern what’s going on with students and think about how I can best support them.”

Words like “empowered” may seem a strange fit for the aftermath of such calamity. However, that is exactly how Clayton-Jones feels when she looks back on it all.

“When those times come, if we are able to channel our energy into walking through it, we come out of it more resilient.”