Inside two concrete buildings at Milwaukee’s Zablocki VA Medical Center, pistons thrust into sleds, steel crumples, and crash test dummies endure impacts. That’s where Dr. Frank Pintar, Eng ’82, Grad ’86, is working to better understand the forces that damage the human body during a car crash. “In order to build a dummy or a computer model of a human, you need basic information about how that human reacts to a trauma situation,” says Pintar, professor and founding chair of the Marquette University and Medical College of Wisconsin Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering.

With funding from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Pintar’s lab is using advanced biomechanics research and measurement technologies to improve crash test dummy design. The lessons learned don’t just help set the injury criteria for those dummies — they inform the vehicle safety technologies and standards that have saved nearly 900,000 lives over the past 50 years.

Sensor Iteration

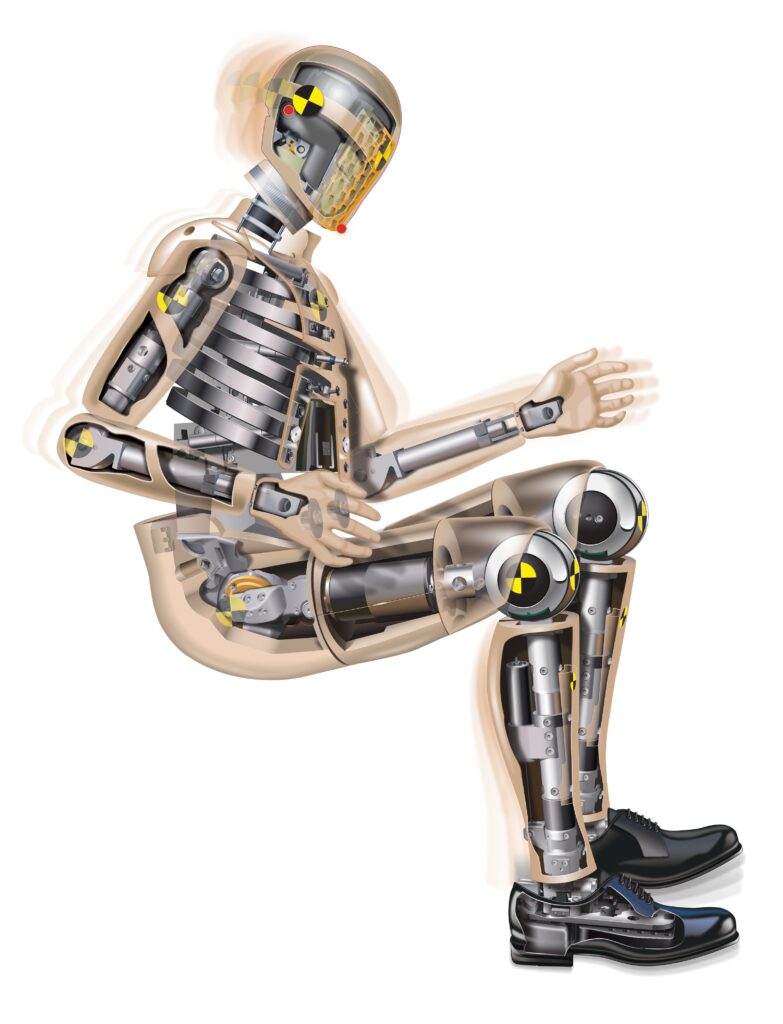

Many different forces can act on the body during a crash — and the latest dummy models contain a dizzying array of sensors to measure them. Load cells in the abdomen and pelvis, for example, can measure the force applied by the seat belt during an impact, while accelerometers in the head and neck measure how quickly those areas accelerate during a crash.

Pintar’s work has helped to improve sensor size, placement and sensitivity. For example, while previous accelerometers in the head only measured movement in a straight line, Pintar and his team discovered that most concussions result from a rotational acceleration. (Think of it like quickly stirring the cream into a cup of coffee.) As a result, manufacturers then developed better rotationally based sensors to measure the impact needed to cause a concussion.

Dummy Diversity

Despite advances in crash test dummy design, most still don’t represent the differences between diverse groups of people, making it more difficult to test if vehicle safety features work for everyone. In response, Pintar’s lab is working to diversify dummy research to account for different body types and sexes.

The pelvis, for example, looks different in men and women, meaning that dummies that represent the female body need to be designed differently. Age-related differences also need to be accounted for, like the fact that the rib cage starts to sag as you age. And differences in weight can be significant too. “This is where the industry is going,” Pintar says. “But we still have to define what the human tolerance is for these particular populations.”

Reflecting Motion

Some dummies in Pintar’s lab are adorned with reflective targets. These targets — coupled with motion-capture cameras — enable researchers to measure how a crash test dummy moves. Then, using computer modeling, Pintar and his team can create a digital replica of the dummy that moves as a human would.

According to Pintar, the future of crash testing may take place in cyberspace. That’s because a digital replica of the human body can be more sophisticated in its measurements. While subtle forces, like the stress placed on bones or ligaments, can’t yet be detected in a dummy, they could be measured by a computer model.

Betting on Biofidelity

Biofidelity — or the degree that dummies can mimic a human response to a collision — is a crucial part of dummy design and a focus of Pintar’s work. For example, during crashes, the researchers learned that if the door crushes into an individual’s hip, it can cause the lower spine to contort into an “S” shape. Yet in earlier crash test dummy models, the spine was too stiff, causing the entire rib cage to move. In response, the dummy manufacturers redesigned the lower spine.

Still, Pintar notes that there can be a trade-off in designing dummies that respond as a human would. “The dummy also has to be robust enough to be able to be used over and over again in a crash test,” he says. “That’s often a big challenge in the design.”