When Dr. Brooke Mayer first set foot on campus in 2012, the Opus College of Engineering was expanding its research expertise and brought Mayer on board as an additional faculty member to specialize in water quality and safety.

“I honestly had never been to Wisconsin before I came to interview,” Mayer says. Having spent her entire life in arid, drought-prone regions of the western U.S., she wasn’t sure what to expect when relocating to the Great Lakes. What kinds of problems would she tackle in a state where water is plentiful?

But as Mayer, now professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering, puts it, “there are water issues everywhere — just different issues.” Coming to Marquette created an opportunity to lean into her interests in water quality and phosphorus recovery research. Now, just over a decade later, her involvement in a wide variety of regional and national water projects has helped establish Marquette as a true leader in the field.

Mayer currently serves as a key research partner and leadership team member for Science and Technologies for Phosphorus Sustainability, or STEPS, a National Science Foundation-designated major research center focused on reducing phosphorus dependence and its downstream effects on the environment. She also recently stepped into the role of principal investigator for the third phase of In Defense of Water, a partnership between Marquette and the Engineer Research and Development Center of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that collectively represents one of the largest collaborative research projects in Marquette history.

The $4.2 million 2024 federal grant funding for this third phase is In Defense of Water’s largest yet and brings total project funding to more than $11 million. Phase three is made up of seven initiatives spearheaded by various Opus College and Klingler College of Arts and Sciences faculty and aimed at improving water safety, quality and emergency response in the event of contamination.

Mayer is in a familiar role fostering collaboration to achieve elevated results. In Defense of Water requires multidisciplinary knowledge, not just from Marquette faculty in environmental and civil engineering and biological science, but also from colleagues who are economists and lawyers. Plus, the help of students and collaborators in the private sector.

Working with broad and diverse teams is Mayer’s superpower. “If I look at everything I’ve ever done, everything is collaborative,” she says. “Even if it’s a project that I’m the sole investigator on, I’m working with students and scholars and postdocs all the way through.”

Thinking outside the box

Early in her tenure at Marquette, Mayer forged an innovative path, earning a prestigious five-year CAREER award for early career faculty from the NSF to investigate new processes for removing phosphorous from the environment and recovering it for valuable agricultural uses. She pioneered advances that inform her work today through the high-profile STEPS project.

Mayer also tackled projects at the Water Equipment and Policy Center, a Milwaukee-based industry/university collaborative research center (IUCRC) funded by the NSF. Dr. Daniel Zitomer, chair of the Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering, is Marquette’s site director of the center and became Mayer’s mentor and close collaborator. Zitomer is also director of Marquette’s Water Quality Center which brings together numerous campus engineers and scientists to tackle research and development in collaboration with industry and other partners.

“There’s been a long train of different types of large, collaborative water research [projects] going on,” Mayer says. Early initiatives gave way to current ones like In Defense of Water. All the while, Marquette’s research arm in the Opus College grew and became more competitive. As part of the university’s Water Quality Center, five professors now work on a close-knit team — and in tandem with some of the largest water research institutions in the country.

Mayer is a “big part of why we are really well known and competitive with much larger universities in these spaces,” says Zitomer.

Each Water Quality Center member has a different specialty, and putting their heads together helps them tackle more expansive and complex projects, Mayer says. Through In Defense of Water initiatives, they also regularly collaborate with colleagues from biological sciences, computer engineering, law, business and education.

“She thinks a lot about not only the research she’s doing and solving water problems, but also how she brings that into the classroom and how we develop future leaders.”

Dr. Kristina Ropella, Opus Dean of the Opus College of Engineering

Researchers from diverse disciplines benefit from seeing new perspectives on shared goals, or being exposed to expertise expressed in another professional language. “By putting these teams together that cross over disciplines, you get much more out-of-the-box thinking,” Mayer says.

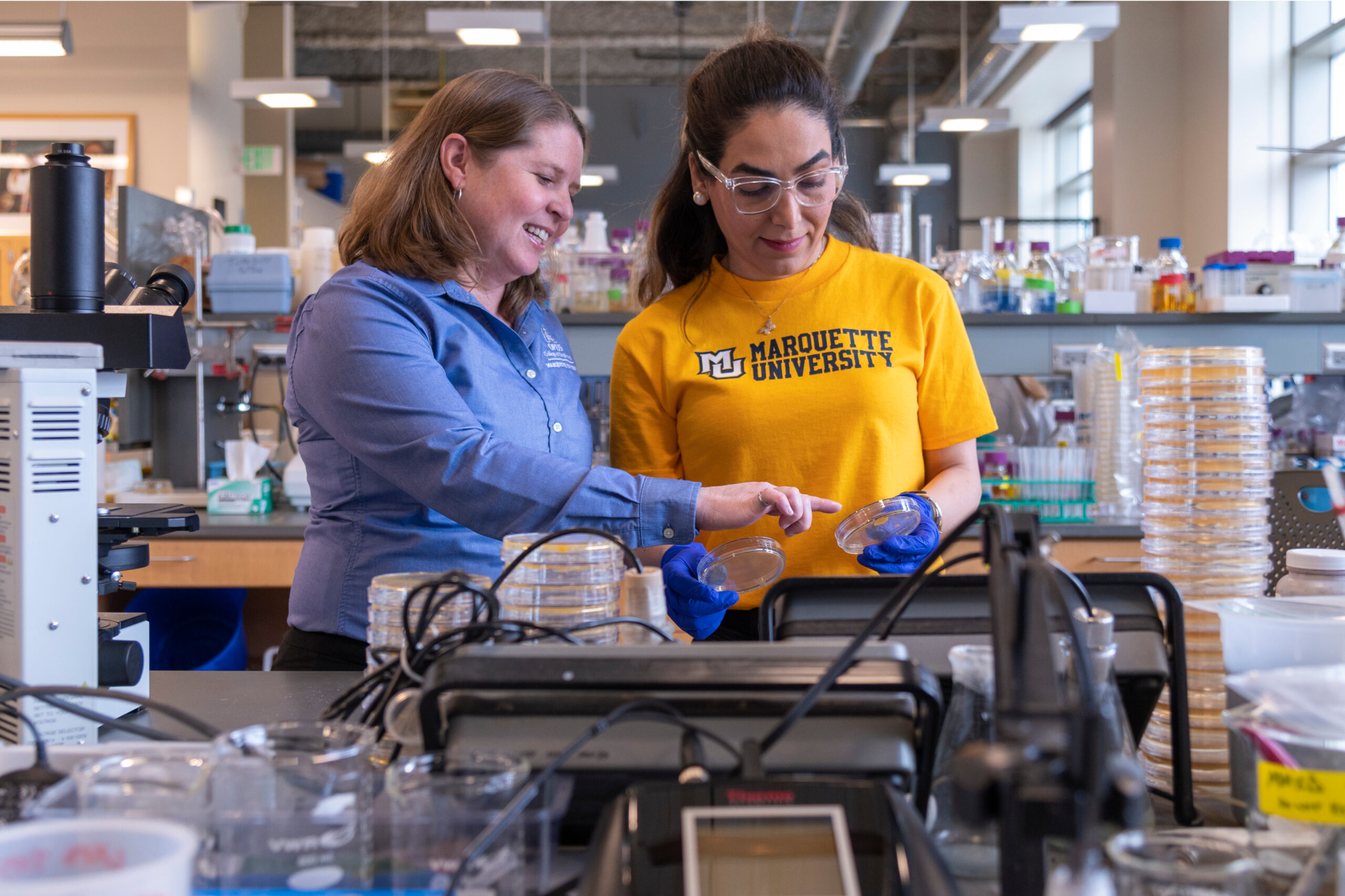

She specifically points to an In Defense of Water project, led by biological sciences professor Dr. Krassi Hristova, that investigates the microbial ecology of biofilms that grow in the sinks, drains and water pipes of commercial and residential buildings. When the research team first got together, members noticed that their approaches, methodologies and terminologies were different. But working together, they were able to learn new approaches to the problem that they hadn’t thought of before. One resulting breakthrough achieved over two phases of the project is testing a UV-LED light source that can inactivate illness-causing microbes while minimizing risks of antimicrobial resistance.

This cross-disciplinary collaboration “really brings about better, deeper solutions to the problems that we’re addressing — in really cool ways that you’d never think about before,” Mayer says.

Building on knowledge

With Phase 3 now in progress, additional In Defense of Water initiatives will build on research from Phase 1 and Phase 2. One such initiative, led by Mayer, focuses on the creation of potable water systems that can remove chemical and microbial contaminants from wastewater to recycle it for drinking and other uses.

Already, researchers have devised a novel method for removing pathogens, excess nutrients like phosphorus, and organic matter from water in a contained system. To devise the technology, they worked in partnership with Rapid Radicals, a local wastewater treatment startup founded by Marquette alumna Dr. Paige Peters. In the third phase, the team will verify their results by reconfiguring and improving an existing test system Marquette researchers built and operate at a wastewater treatment plant in Milwaukee.

These systems could have applications for military and civilian use in areas where fresh water is not plentifully available. As with other projects funded in multiple phases, new funding will allow Mayer to take her technology into the field to see how well it performs in real-world conditions.

Training the next generation

When she’s not developing cutting-edge solutions to some of the most pressing water problems of today, Mayer is focused on sharing her knowledge with the next generation of leaders.

“She thinks a lot about not only the research she’s doing and solving water problems, but also how she brings that into the classroom and how we develop future leaders,” says Dr. Kristina Ropella, Opus dean of the Opus College of Engineering.

As co-director for education and human resources for the STEPS center, Mayer helped create a student leadership council and mentorship program for students from 11 institutions across the U.S. At Marquette, she honed her leadership skills with the E-Lead program during a special session that welcomed faculty participants, and she is currently an ELATES fellow at Drexel University. The prestigious program focuses on enhancing the leadership skills of accomplished female faculty in STEM fields.

Outreach and teaching matter a lot to Mayer, who had many “terrific” mentors throughout her career. “I can attest to the tremendous positive impact that these connections have had on me,” she says. “I hope that I can share these same gifts with others to help support future generations with advice, feedback and support.”

Mayer says that her leadership style isn’t just one static thing — it’s always evolving. “The longer that I’m in these different roles, the more that I learn about strengths that I have, but also weaknesses, areas of improvement that I have, and where others have different and complementary strengths,” she says. “Learning to leverage those better has been a wonderful experience, and very eye-opening for me.”