Borsuk’s essay and all colleague reactions are available at this link.

Alan Borsuk is dismayed by what he sees as lack of progress in educational achievement. He cites, especially, undiminished group disparities in recent years, and he lists a promiscuous assortment of reforms that do not appear to have accomplished much. Results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress over the last two decades tend to confirm his concern. Yet stasis determined by a single measure of progress during a relatively short time frame runs the risk of overlooking differences that reforms have made. It lends credibility to the sentiment that the government does not have a proper role in equalizing educational opportunity or, more insidiously, that the persistence of unequal achievement traces to the deficiencies of low-income, Black, Latino, and Indigenous children and families, rather than to how schools and other institutions have failed them. Such a perspective justifies underinvestment in those who have been provided the least. Of course, Borsuk simply means to stress the inadequacy of reforms.

Taking a longer view, however, what is striking to me is how much change, albeit insufficient, has taken place since Brown v. Board of Education—despite major educational reforms that have been compromised or ill-considered and in the absence of family-supporting policies that would promote learning. Changes in Black attainment illustrate this most powerfully. In 1960, for instance, 21.7 percent of Black adults in the United States had graduated from high school, as opposed to 43.2 percent of whites. Yet in each subsequent decade, the percentage for each group increased and the disparities narrowed, until Black graduation reached 88.8 percent in 2019 and white graduation rose to 94.6 percent. College graduation has a similar trajectory. In 1960, 3.5 percent of Black adults had a bachelor’s degree, as opposed to 8.1 percent of whites. By 2019, the numbers were 26.3 percent and 40.1 percent.

Much of the explanation for this transformation initially involved matters outside of schools—the Great Migration and access to higher-paying jobs in the North; the civil rights movement that spurred the legal prohibition of discrimination in the 1960s; and the War on Poverty’s social safety net that, on a less discriminatory basis, modestly expanded the protections forged by the New Deal. But school desegregation mattered as well. The Black struggle to end segregated schools was an assertion of human dignity and an effort to gain access to the same educational resources that whites enjoyed.

Few white people were willing to share those resources, however. Resistance ranged from the creation of voucher programs in southern states to subsidize racially exclusive academies for white students; to mob intimidation and violence in Little Rock, New Orleans, and Boston; to massive white flight from urban schools. And when desegregation did take place, it typically occurred on terms favorable to whites. Thousands of southern Black teachers and principals lost their jobs; the burden of busing largely fell on Black students; magnet schools with an abundance of resources were designed to attract white students; and Black students were segregated in less challenging courses through tracking. Where desegregation exists today, tracking and racially disproportionate disciplinary action remain significant problems, but a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions guaranteed that desegregation would be limited. Most importantly, Milliken v. Bradley (1974) essentially immunized suburban schools from desegregation orders, and Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No.1 (2007) cast doubt on the legality of even voluntary desegregation.

Despite all of this, achievement disparities closed dramatically over the years when desegregation was most robust, and research demonstrates that desegregation itself strongly contributed to Black achievement.

President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty ushered in an era where education became the chief policy to remedy poverty and inequality, displacing more direct means, until the response to the COVID epidemic at least momentarily changed this at the federal level. The War on Poverty featured two less redistributionist and longer-lasting reforms than desegregation; in fact, they rested easily with segregated schools. Head Start has provided preschool for low-income children since 1965 and always has been limited in effectiveness by very low salaries for teachers, many without degrees. The original Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965) provided thinly distributed additional resources to schools with low-income students, initially delivered to them in pullout programs at the cost of regular instructional time and ultimately through schoolwide practices. Although neither program affected test-score disparities, both have contributed to a modest improvement in high school graduation and positive adult outcomes.

A potentially more robust way of equalizing educational opportunity for poor children was driven by a Mexican-American effort to equalize funding between rich and poor districts, but it failed at the Supreme Court, which ruled in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) that education was not a constitutional right. Decades of arcane litigation and legislation followed at the state level, which generally did lead to greater equalization, but this was often compromised, in part by legislative resistance influenced by the opposition of wealthy districts. Nonetheless, these financing reforms have been associated with academic gains, especially where funding to low-income districts has been the most generous.

As schools began to resegregate, most consequential educational policies were severed from the idea that additional resources should flow to those in the most need. One major emphasis was standards and accountability; this was epitomized by No Child Left Behind. Oblivious to unequal conditions within and outside of schools, it assumed that if educators were driven to work harder by the threat of penalties when any demographic group underperformed, educational outcomes would equalize for all groups. This drove teachers in major urban districts to ignore subjects beyond the tested ones of reading and math, while narrowing their pedagogy to drill and test preparation. More homogeneous affluent districts, in contrast, escaped sanctions and carried on with their much more enriched curricula.

School choice also is predicated on the assumption that lack of resources isn’t the cause of educational inequality, but rather lack of competition is, and dollar amounts attached to vouchers and charter schools typically are far less than conventional per-pupil expenditures. Choice legislation has had little effect on affluent suburbs where parents can assume quality education as a right, while in major urban districts Black and Latino students are merely given the right to compete for a quality education in a marketplace where the supply of high-performing schools is scarce and elite suburban and private schools are mostly off limits. Some form of choice is now pervasive in many urban districts, but choosing equality is elusive.

Finally, recent “science of reading” legislation in many states assumes the problem isn’t resources but rather how teachers teach. The so-called “Mississippi miracle” perfectly illustrates this—impressive gains in fourth-grade reading despite per-pupil funding that is the sixth lowest in the country and one of the flimsiest social safety nets as well. Like Borsuk, I am skeptical. Third graders who are unable to pass a reading test are held back, and currently Mississippi eighth-grade reading scores are lower than in 38 states and only two points higher than they were in 1998, with essentially the same Black/white disparity. It would not be surprising if instruction of students in low-income schools, where Black students are concentrated, overemphasizes phonics and phonemic awareness at the expense of language-rich environments that the science of reading actually supports.

Desegregation long ago dropped from the educational policy agenda, yet the problem of segregation remains. This is not because schools are Black or Latino, but, as recent research has shown, because many are also poor, and poor people’s schools typically provide a poor education, foremost because they cannot attract high-quality teachers. Consequently, those who face the most difficult circumstances outside of school also generally get the worst schools. Substantially greater funding for these schools would not guarantee that it would be used to hire academically and pedagogically accomplished teachers, that there would be an intellectually engaging curriculum in a high-demand/high-support environment, and that there would be “a sympathetic touch between teacher and pupil” to use W. E. B. Du Bois’s phrase. But without such funding, the possibilities for change are severely limited. The logic of recent reform, in any case, does not support a funding-focused effort, nor is there the political will to pursue it.

The turn away from a redistributive approach to educational reform can be reversed and amplified, but current social norms that promote individualism, personal responsibility, and the unlimited accumulation of wealth do not encourage this. In fact, since the economic returns to education have become increasingly high in the United States, those with power and privilege are incentivized to hoard superior educational opportunities for the credentials that will preserve the status of their children.

The history of school reform since Brown demonstrates, in any case, that small increases in opportunity have historically made a difference, but if we want to see dramatically more equal educational outcomes, we’ll need to have a more equal society. Perhaps the best educational reform in recent years wasn’t an educational reform, but President Biden’s short-lived Child Tax Credit expansion, which reduced child poverty by nearly 50 percent.

Illustrations by Robert Neubecker

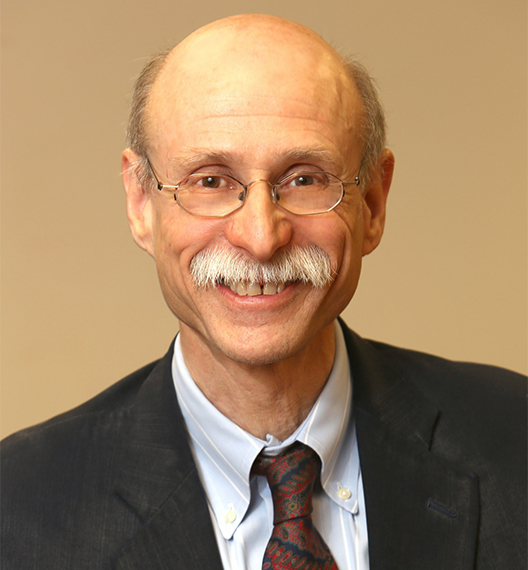

Robert Lowe is a professor emeritus at the Marquette University College of Education. He holds a Ph.D. from Stanford University; his research has generally focused on race, class, and schooling in historical perspective.