Heat waves carry risks that go far beyond dehydration. Even the reproductive system is affected by extreme temperatures, which could spell danger for future generations. “It is well documented that climate change is affecting human fertility already,” says Dr. Lisa Petrella, associate professor of biological sciences. Birth rates drop nine months after a heat wave, and stillbirths have also been linked to prolonged temperature increases.

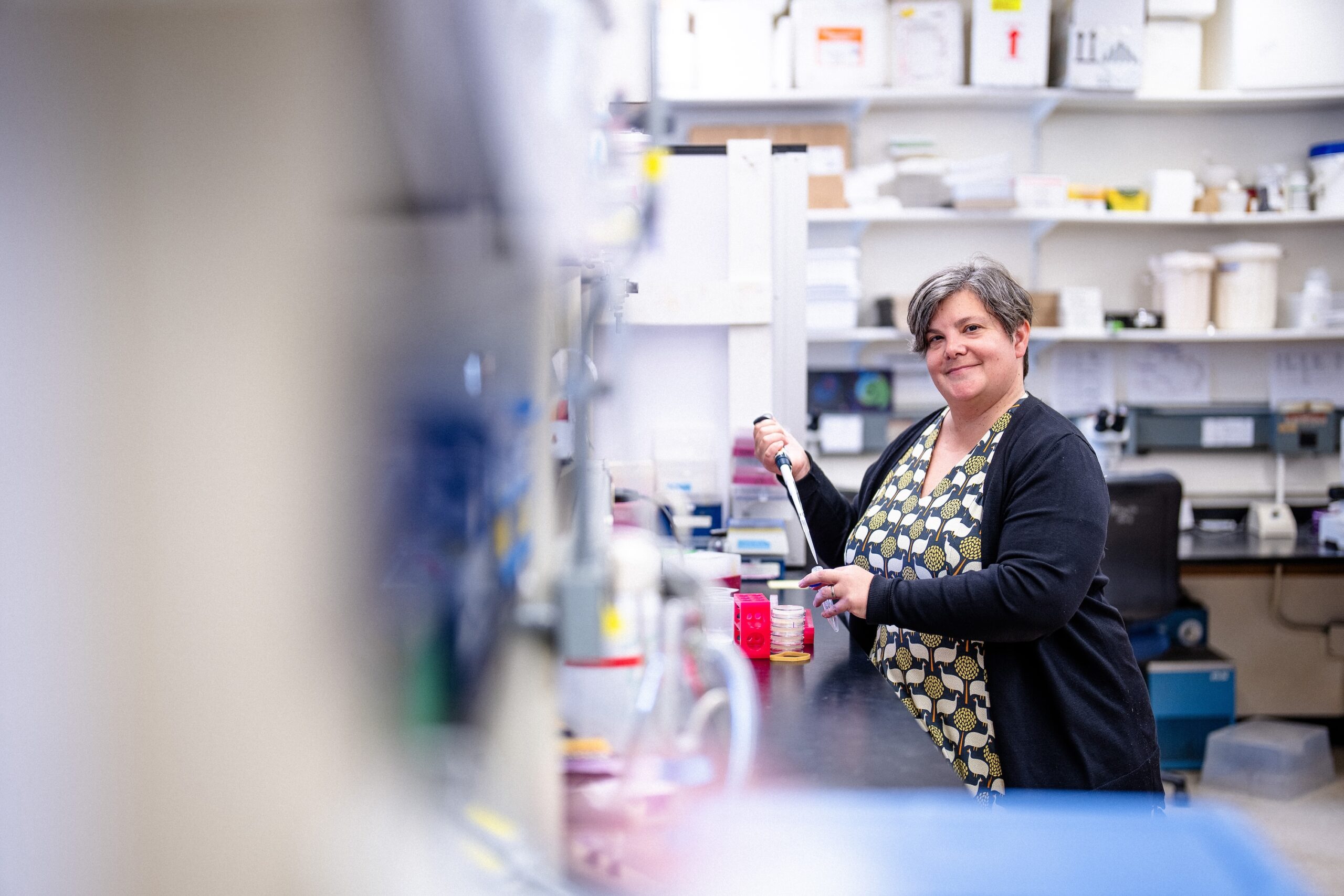

One organism is helping to reveal the causes behind this worrisome link: the humble nematode. Petrella’s lab has probed the connection between temperature and sterility in these microscopic creatures for over a decade. With support from a $460,000 award from the National Institutes of Health, Petrella is investigating reproductive cellular changes that could hold the key to climate resilience.

Oil and Vinegar

We all know what happens when a sperm and egg cell meet. But before those sperm and egg cells exist, they start out as germ cells — specialized packages of material that guide embryonic development and pass genetic information to the next generation.

In nematodes, germ cells are nearly identical in structure to those found in humans. That’s why they’re ideal model organisms for studying the effects of heat on fertility.

Petrella’s most recent project narrows in on two structures in germ cells — P granules and the synaptonemal complex — that play a critical role in making sure embryos get the right number of chromosomes and grow properly. But these essential structures are liquid-like and delicate. Petrella compares both to drops of oil in vinegar. Just as the two substances mix but never fully integrate in a salad dressing, the microscopic structures that contribute to fertility maintain separation in the germ cell’s gooey cytoplasm, especially when experiencing typical temperatures.

Melting Away

In past research, Petrella’s team discovered that some species of nematodes can successfully reproduce at high environmental temperatures, while others lose their ability to create healthy offspring. It’s not yet clear why this happens, but Petrella and fellow researchers are getting closer to answering the question: What makes an animal’s fertility more hardy in the heat?

By observing how germ cells change in nematodes as the temperature creeps up, she aims to pinpoint an underlying cause of fertility loss in many species. Petrella’s team hypothesizes that the P granules and synaptonemal complex may actually “melt,” or be absorbed back into the cytoplasm when exposed to high heat. Without them, species become functionally sterile.

Answers about resilience could lie in the architecture of the germ cells. In addition to understanding what happens to the P granules and synaptonemal complex under pressure, Petrella is exploring the differences between the biological building blocks — proteins — inside each structure. Those gritty details will reveal why some nematodes can take the heat, while others can’t.

The Climate Connection

Petrella’s work has far-reaching implications for survival in the era of climate change. Her work aims to pinpoint how heat stress damages even the smallest reproductive structures in the body, causing a domino effect that could lead, in extreme scenarios, to entire species going extinct.

Record-breaking temperatures are only becoming more common in modern times. The frequency, length and intensity of heat waves have increased over the past 70 years — and with that, the threat to fertility also rises. But by digging into the finer details, Petrella hopes that the knowledge gained can help safeguard vulnerable life-forms on a warming planet.

While her lab exclusively works with model organisms, her findings could be extrapolated to many species in the animal kingdom. Humans are just one of many groups that have similar germ cell architecture to nematodes. And with heat waves having a tangible impact on fertility in many animals, including honeybees, cows and fish, knowledge of germ cell structures could help crack the code of broader patterns in biological resilience.

Why It All Matters

The sooner researchers can understand how heat impacts animal reproductive systems, the sooner they can identify and protect vulnerable species across the animal kingdom. Uncovering the biological mechanisms that make some more susceptible than others to heat could help scientists predict which species may become endangered — and how certain ecosystems will fare if populations shrink or vanish.

Petrella also hopes that other research teams will use the results of her work to design interventions that help vulnerable species. That could mean designing drugs to increase the chances of conception in some species, but it could also mean turning an eye to the needs of the smallest animals that uphold ecosystems worldwide. Even microscopic organisms, like nematodes, are at risk, and they would have a massive impact on the world if their numbers shrank. In the wild, these microscopic organisms break down decaying matter and turn it into nutrients that plants absorb to grow. ”We need to be worried about these small organisms because these are the organisms that recycle everything,” Petrella says.