When Alex Gambacorta left the Apsáalooke Reservation in Montana, she thought she was closing a chapter on the special place she’d served for a year. But back at Marquette, pieces of Apsáalooke history were waiting to be discovered — and a new journey with the tribe was about to begin.

Red Star. Big Day. Plainfeather.

Alex Gambacorta recognized these surnames written more than a hundred years ago in sloped cursive.

She didn’t expect to see them here, some 1,100 miles away from the Apsáalooke (Crow) Reservation, on a piece of paper in the archives of Marquette’s Raynor Library.

These names belonged to the students Gambacorta had taught at St. Charles Mission School in Pryor, Montana, three summers earlier. Poring over dozens of archival documents and photos, she realized they showed her students’ ancestors — and, in some cases, their living grandparents.

Gambacorta, Arts ’18, Grad ’23, admits this discovery was a rather serendipitous case of being in the right place at the right time.

Going to the library that week in 2021 with fellow students from her English course, she had watched with amazement as Amy Cooper Cary (head of archival collections and institutional repository) held up a document from Pryor to show the class: a letter written in 1924 from Apsáalooke parents petitioning the powers that be to establish a Catholic day school.

Cooper Cary pulled this letter out of hundreds of possible selections without knowing Gambacorta’s connection to the community.

She selected this particular letter because it was unusual. Most of the archive’s massive collection relating to Catholic missionary work was correspondence with clergy. To have a letter written, signed and thumb-printed by the Apsáalooke was rare.

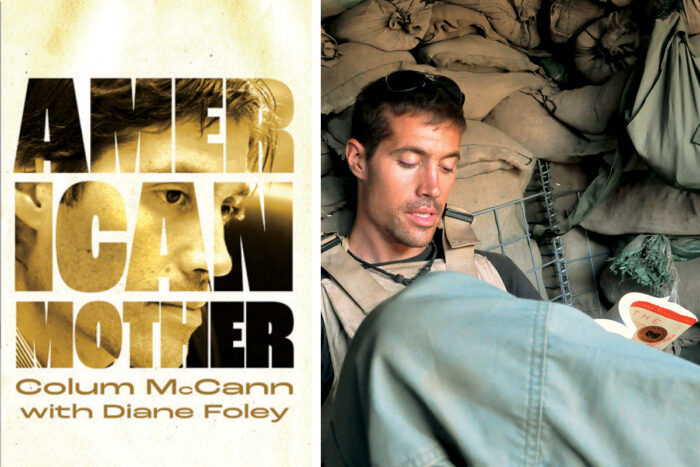

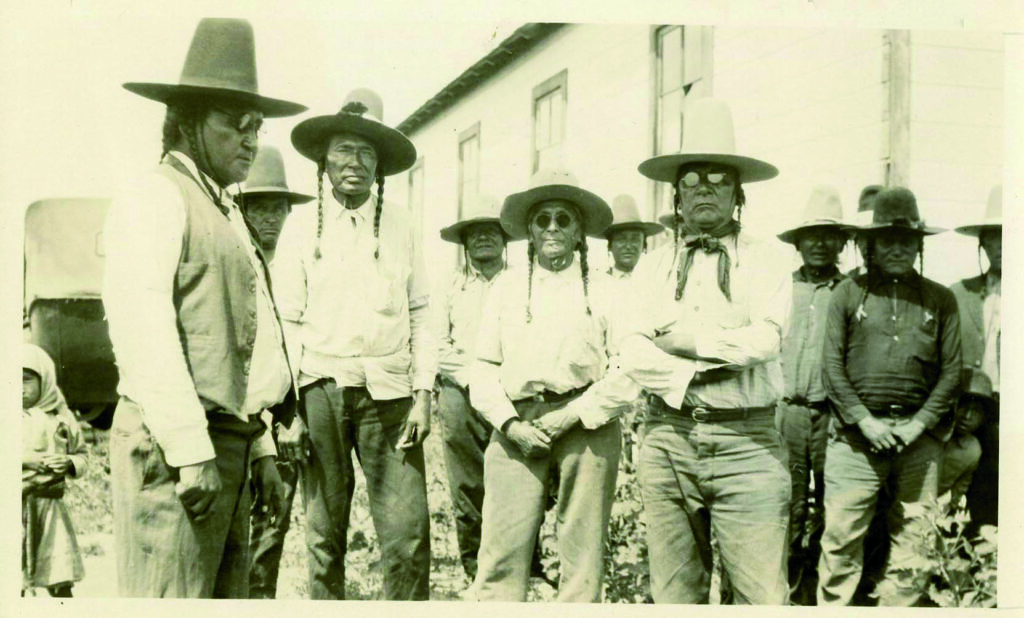

The caption to the left accompanies the photo to the right — and pictured in the far right is Pauline Plainfeather, beloved ancestor of Fannie Cliff. On the left is Elizabeth Round Face and in the middle Mary Plain Bull, all students at St. Charles School. (photos: Series 9-3, Box 7, Folder 5, Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records, Special Collections and University Archives, Raynor Library, Marquette University).

When Cooper Cary concluded her remarks, Gambacorta approached the letter and locked eyes with her professor. “I remember Alex’s surprise. This, of course, set off quite the chain of events,” says Dr. Samantha Majhor, assistant professor of English.

Gambacorta returned a few days later, asking Cooper Cary, “Can you show me the box where this letter came from? Is there more?”

Indeed, there was more.

Fifty boxes more.

As she began flipping through them, Gambacorta was transported back to the days after her graduation from Marquette when she had joined the Jesuit Volunteer Corps Northwest and served at St. Charles as a reading intervention specialist. “I did anything that was needed,” she remembers. “Academic support, tutoring, reading and writing, sometimes gym class.”

Now, these records showed her the school’s origins: nuns teaching a handful of Apsáalooke children in a small chapel in 1892; the emergence of a day school that grew into the version of St. Charles she had come to know intimately — a mission school combining its Catholic and Indigenous roots, teaching both spiritualities and enrolling over a hundred students for preschool through eighth grade.

“To bring family history back into the family itself is particularly healing for the Native community, whose histories remain obscured in the national narrative.”

Dr. Samantha Majhor, assistant professor of English

Page by page, photo by photo, something started shifting in Gambacorta. Majhor’s course, Native American Literature and the Indigenous Archive, was one of the first classes in Gambacorta’s master’s program in English. Given the time she’d spent in Pryor, she had been looking forward to the course content, but her decision to enroll had been happenstance. Days into her first semester, she hadn’t expected to be diving into a subject that so strongly compelled her.

She had found her master’s professional project — and she had located a trove of historical family photos that the Apsáalooke community had never seen. She knew she had to try to reunite them.

As one of Marquette’s largest archival collections, the archives relating to U.S. Catholic Indian missions clocks in at nearly 500 cubic feet, or almost two football–field lengths worth of material. This includes letters between clergy and administration; clergy and tribal chiefs; Catholic missionary publications; and photographs — including posed images of baptisms, first Communions, confirmations, nuns with their classes, and day-to-day tribal and missionary life.

With hundreds of tribal nations in the U.S., such a vast amount of Catholic missionary material makes sense. But the fact that Marquette holds the nation’s largest archives on Catholic missionary work with Indigenous communities comes as a surprise to most. Originally residing in Washington, D.C., the records in the archives were amassed by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, a religious entity seeking to evangelize Native Americans. The bureau has been involved with a significant network of schools and churches since the 1870s. The records came to Marquette in 1977 through the advocacy and persistence of Rev. Francis Paul Prucha, S.J., whose prolific research specialized in U.S. policy on Native Americans.

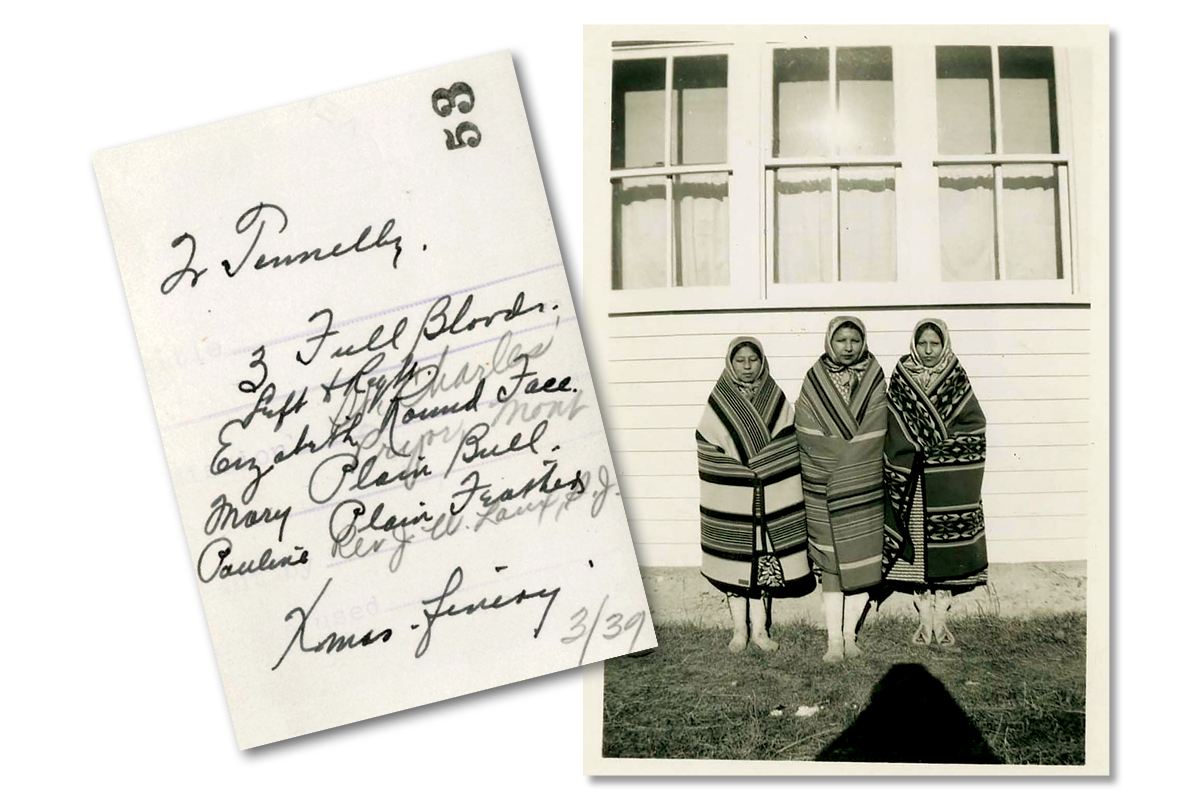

Cliff’s great grandfather Plainfeather is in the front row, second from left, above, with Chief Plenty Coups third from left in front. (“Chief Plenty Coos after church, 1925.” [written on verso] Series 9-1, Box 28, Folder 14. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Archival Collections and Institutional Repository, Raynor Library, Marquette University).

Today, this rich history is gaining interest — and the archives, more visits — from Marquette students and faculty. This includes members of the Indigeneity Lab that Majhor, of Yankton Dakota and Assiniboine descent, helped found in 2021. The lab offers opportunities for undergraduates to collaborate with Native and non-Native faculty members on Indigenous research topics. And one of those projects, mentored by Majhor, involves using the archives to increase awareness of boarding and mission schools, some of which have had reported cases of student abuse, poor health conditions and student deaths.

As Gambacorta began gathering Apsáalooke archival material outside of class, Majhor recommended Gambacorta conduct her work in partnership with the lab. Gambacorta’s passion project landed her an inaugural graduate assistantship, and they got to work.

Gambacorta knew what she had to do next, but she was nervous.

She had to cold-call a beloved Apsáalooke community member, Fannie Cliff, to ask whether the photos were something the community would even want to see.

The question met a happy answer.

“My answer was yes — I was excited to see them. Photos are good,” Cliff says. “My friends had informed me about Alex. They said she was a lot of fun. A little crazy,” Cliff says with a twinkle in her eye.

Above, from left: Alex Gambacorta, Fannie Cliff and Dr. Samantha Majhor, speaking at Marquette in February 2024. (Photo by Alex Nemec).

After they talked on the phone, Gambacorta agreed to fly out to Pryor to meet Cliff in December 2022 and show her the photos in person. It’s an occasion Gambacorta and Cliff aren’t likely to forget. When Gambacorta started clicking through photos on her laptop, Cliff immediately recognized her great-grandfather Plainfeather along with renowned leader Chief Plenty Coups in a group photo. And then, spotting a strong family resemblance, she realized the face in another photo belonged to a beloved family member, Pauline. Pauline was her mother’s aunt, and this was the first time Cliff had ever seen a photo of Pauline: “This is my Kala’a Pauline. I became very emotional and happy that I finally was able to find a picture of her, as my mother always talked about her. She would be so delighted to finally have a photo of Pauline.”

“This all was a happenstance of the Lord having put Alex in the right place at the right time,” Cliff relays.

Wanting others in the Pryor community to see their own family photos, the pair decided to hold a community event in May 2023, and to start spreading the word. Time was of the essence, as Apsáalooke elders continued to age and struggle with illness: “It was important to me that we connect photos with their families, as a lot of our elders passed away during the pandemic,” Cliff says.

Cooper Cary and a student carefully scanned the needed photos.

Gambacorta, university colleagues and friends — Dr. Jacqueline Schram, director of public affairs and special assistant for Native American affairs, Majhor, Dr. Jodi Melamed, professor of English, and Indigeneity Lab members — made hundreds of photocopies of these scans.

And in the hopes of a large turnout, they decided to elevate the event.

Cliff helps to identify names at the community event in Pryor.

“Fannie wanted this to be a celebration,” says Gambacorta. It quickly evolved into an Apsáalooke powwow — with home-cooked steaks, fry bread, drumming, a contest to best perform the tribe’s traditional push dance, and invitations sent far and wide to tribal leaders — some of whom traveled across the state to be there.

“We started with prayer, honored our military, brought in clan flags and sang our flag song,” Cliff explains. “The push dance contest helped encourage families to come and look at the photos.”

The event drew more than 130 people, and many individuals were identified in the photos presented, with some elders even identifying themselves. “People laughed, and they cried, and they wished that they had more photos,” Cliff says. Among many emotional moments, some elders with Alzheimer’s had moments of lucidity and were able to identify family in photos, as well.

Majhor elaborated, “To bring family history back into the family itself is particularly healing for the Native community, whose histories remain obscured in the national narrative.”

A binder of photocopies of all known archival photos now resides at Chief Plenty Coups State Park Museum and Archive in Pryor, with Cliff continuing to meet with Apsáalooke families to hold space for this important identification and reunification work. “Archives, especially extensive ones, tend to be invisible, if not intimidating,” Majhor says. “Our goal is to raise awareness that these records and this history exists and help bridge between the classroom and the archival space.”

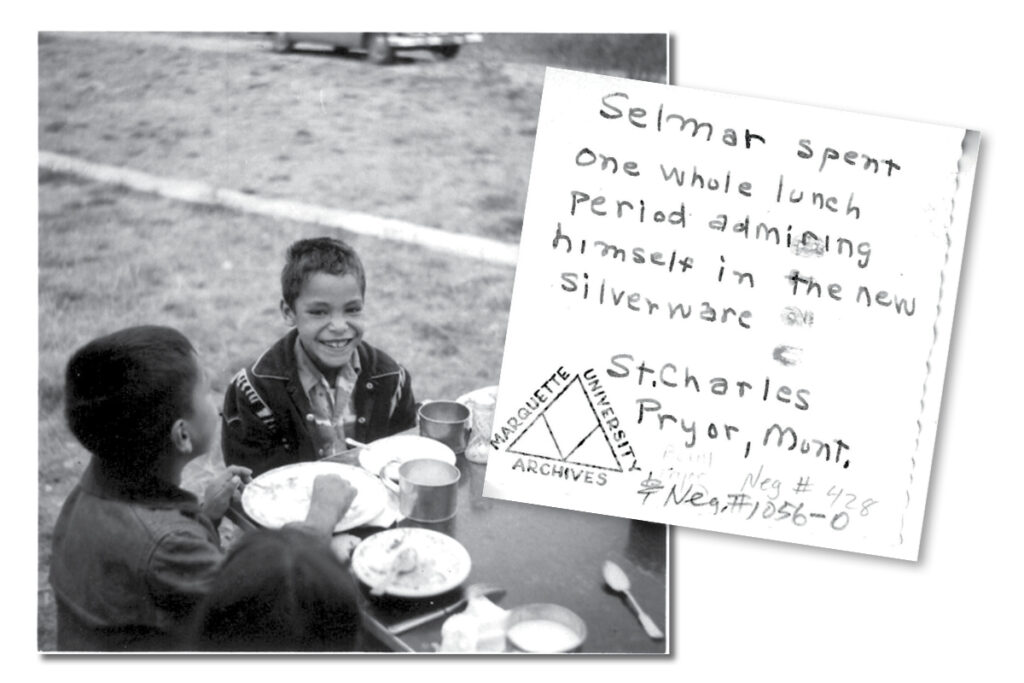

Selmar Red Star, smiling above, fondly remembers this photo being taken. Gambacorta knows Red Star’s grand-children who attend St. Charles. (Box 28, Folder 14. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Archival Collections and Institutional Repository, Raynor Library, Marquette University).

Gambacorta has also reflected on what this experience has meant for her. Reminded of her grandparents’ kitchen table and the photos she’d been shown to learn her own Italian heritage, she remarks, “How can you put that feeling into words? This cannot just be seen as history for preservation,” adding, “When you think about the context of these family photos being housed in an institution, there are still many more conversations to be had.”

For all her efforts and her joyful spirit, Gambacorta has been welcomed back into the Apsáalooke community in more ways than one. During a blanket ceremony last year, she officially became Fannie Cliff’s adopted sister. “We saw Alex’s good heart and how she allowed herself to be open to our people, including her generosity and her heartfelt actions for our kids,” Cliff says. “She was adopted into the Greasy Mouth Clan and is child of the Greasy Mouth/Sore Lip.”

“There was a receiving line where everyone greeted me as part of the tribe and the family. It was very emotional,” Gambacorta responds.

Majhor and others involved look at the model of reunification Gambacorta started as a pathway for the future. With numerous tribes and records to go, this project is indeed only the beginning.

Featured photo by Mike Miller

For more information, visit: