Lexee Torchia has been around people with disabilities for most of her life — it fueled a deep desire to help them.

From kindergarten through fifth grade, Torchia was a “class buddy” for her autistic friend. Every day, she would accompany him through school; on Thursdays, she would bring him to the guidance counselor’s office to play games. It was only years later that she realized these games were actually occupational therapy exercises.

As a teen, Torchia went on to work with children, teenagers and adults at Warren Special Recreation in Gurnee, Illinois. She also witnessed her grandma’s life change from Alzheimer’s disease — as it progressed and her abilities declined, it limited where they could spend time together.

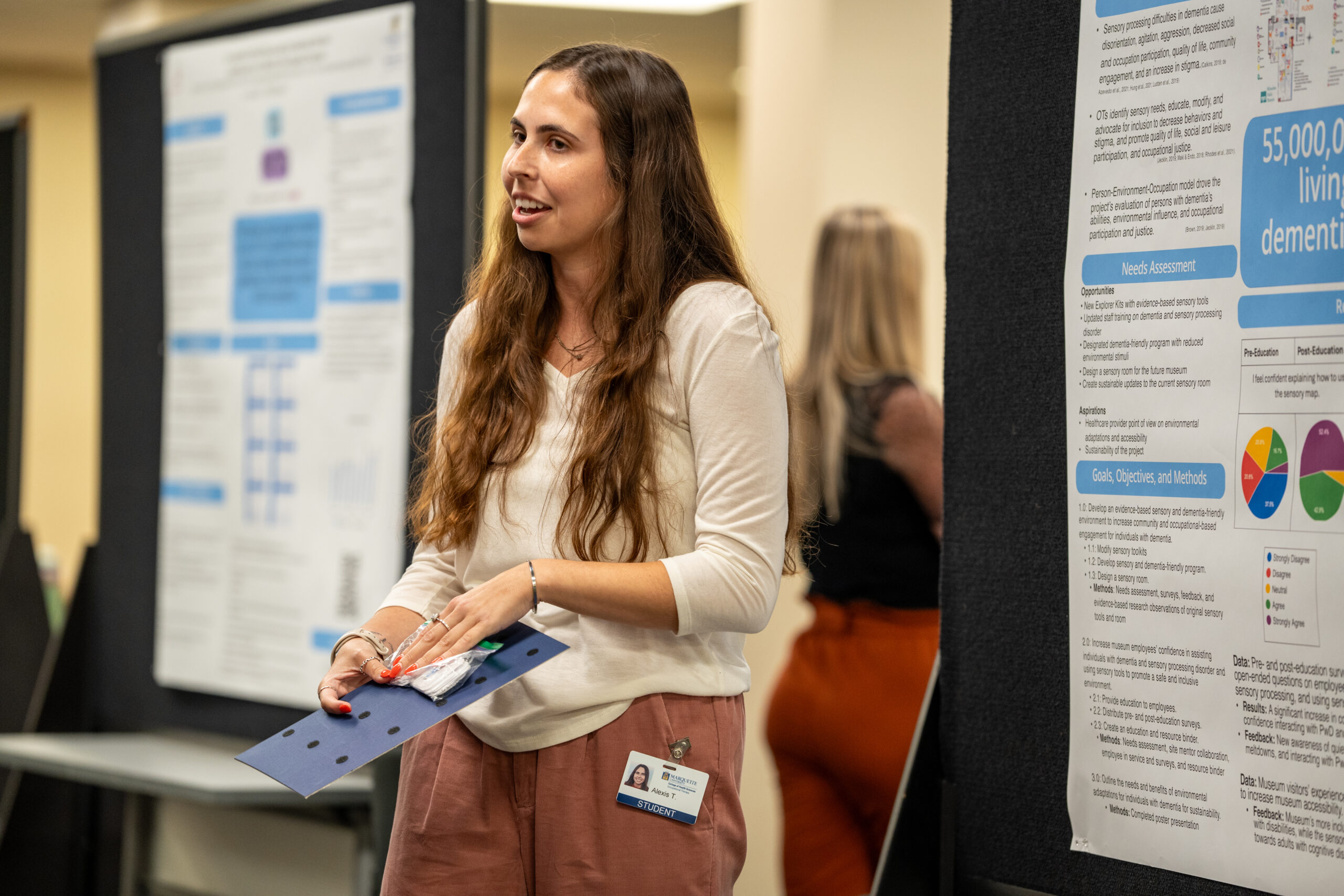

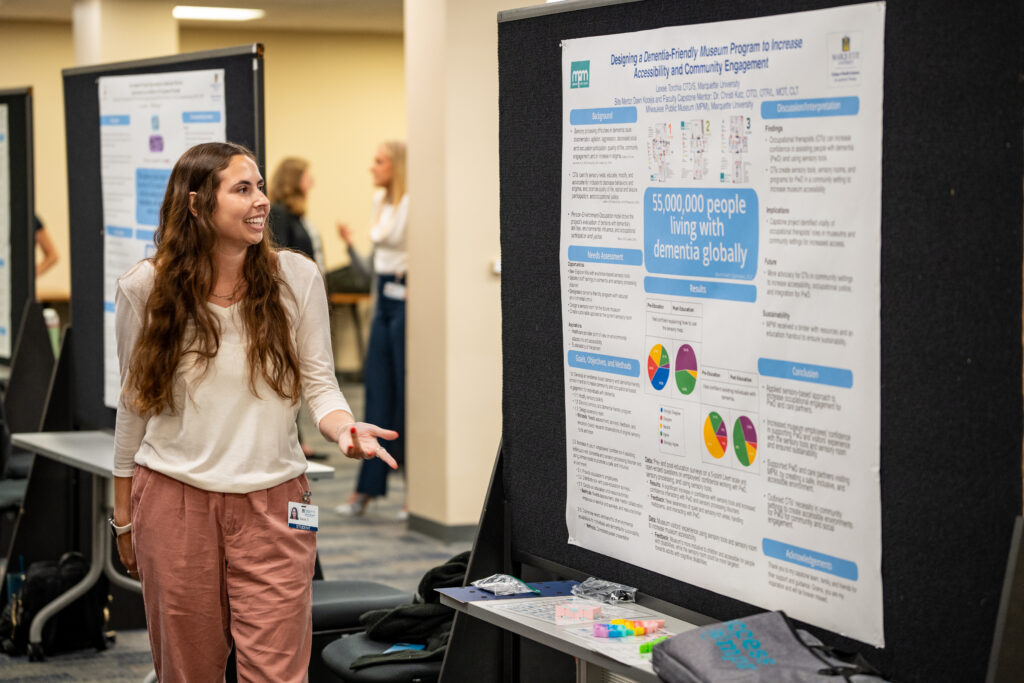

Ultimately, this inspired the recent occupational therapy graduate’s doctoral capstone project: she enhanced dementia-friendly programming to increase accessibility and community engagement at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

“My grandma and I would go to the same restaurant or certain spaces that we knew she was safe where people weren’t judging her and she felt included,” Torchia says. “I wanted to see how I could do that in a community setting and if I could go to a museum and make people like my grandma more comfortable.”

Dawn Koceja, Milwaukee Public Museum community engagement and advocacy officer and Torchia’s site mentor, says she first met Torchia when she and other Marquette students visited the museum to discuss accessibility.

“Immediately, Lexee was excited about the work we were doing,” Koceja says. “We both shared our enthusiasm for what we could learn from the experience, not only for the two of us, but also for the visitors we serve.”

While Torchia’s capstone project initially focused on making things more accessible to people with dementia, it quickly had a ripple effect across the museum.

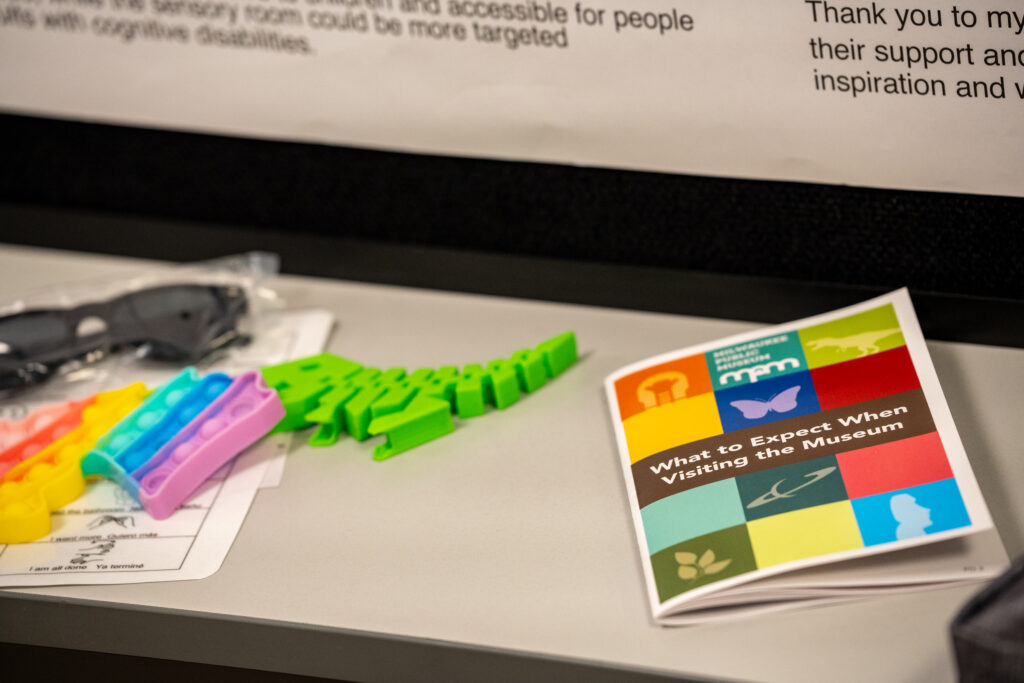

“I would talk to people and they told me they wanted the sensory room to be more adult-friendly as it was aimed mostly at kids,” Torchia says. “From that, I designed and proposed sensory-friendly programming and maps so all visitors with a disability knew what to expect when they visited the museum, whether that was loud noises in an area, overwhelming smells or anything else triggering. We wanted people to be comfortable when they entered the museum.”

Torchia and Koceja brainstormed ways to provide more services and materials that are now available for visitors, including making displays screen reader accessible, supplying sensory lab coats for visitors to wear and creating sensory kits.

Torchia also designed a sensory room and created a complete plan for that space in the new museum facility, which is set to open in 2027.

Torchia’s efforts are the basis for a new initiative in public museums, one that Koceja says is more inclusive of the 25% of Americans with a disability.

“Oftentimes, museums have a ‘look, don’t touch’ expectation, but we are hoping to change that to meet the needs of these individuals,” Koceja says. “We need to continue to develop opportunities for people of all abilities which can be done through creating accommodations and tools without changing museum exhibits.”

Koceja says she has never in her 18-year career at the museum been more excited to see the growth and potential of a student, praising Torchia’s ability to lead staff trainings and navigate challenges.

“Lexee learned how to bring occupational therapy outside the medical environment and into nonformal educational destinations,” she says. “We also hope medical professionals will consider using or promoting spaces like museums and incorporate those experiences into therapy opportunities.”

Torchia says the biggest lesson she learned during her capstone project is that occupational therapists can have a role anywhere and do not necessarily have to work in a hospital or clinic.

“Occupational therapists can make a big difference outside of formal health settings,” she says. “Our profession has an important role in advocating that more public spaces be accessible and in finding solutions to ensure accessibility in every environment.”