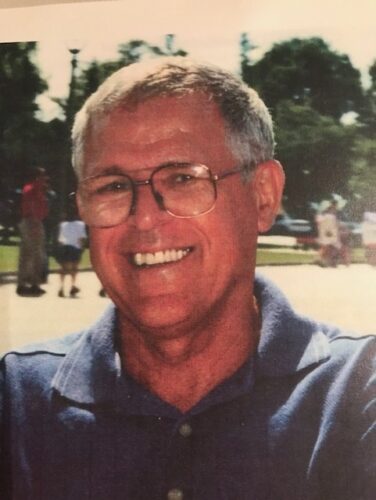

Nobel laureates Dr. Victor Ambros and his colleague Dr. Gary Ruvkun were awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering a completely new way genes are regulated. They uncovered “microRNAs” — small RNA molecules that can act like genetic switches. This work changed how scientists understand gene control and revealed new insights into diseases like cancer.

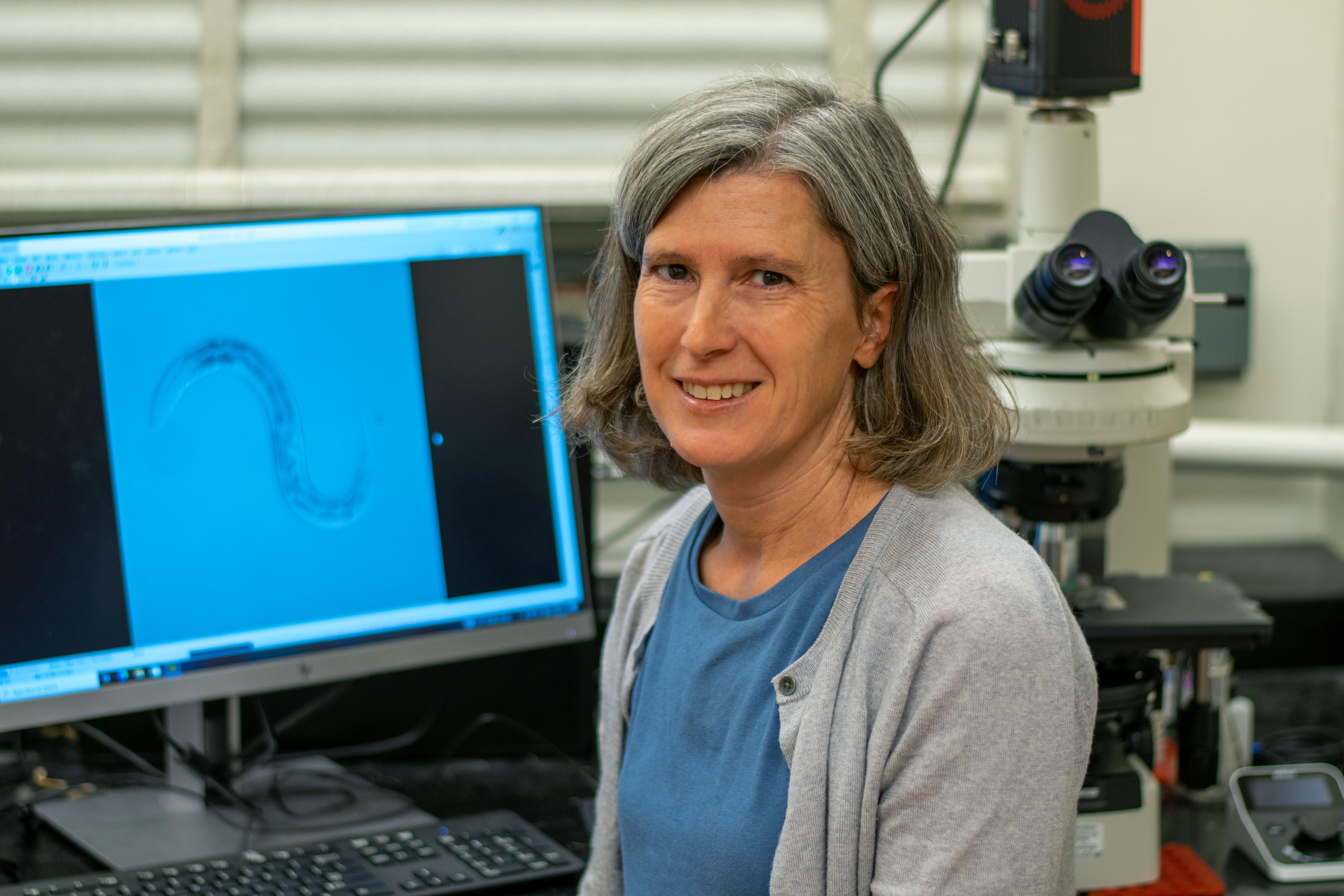

Dr. Allison Abbott, associate professor of biological sciences in the Klingler College of Arts and Sciences, continues to explore microRNA research. In a Q&A, she reflects on her time in Ambros’ lab, the impact of his work, and the importance of following one’s curiosity.

What achievement earned Ambros the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine?

Dr. Ambros’ Nobel Prize celebrates his discovery of microRNAs and their role in controlling gene activity. His research uses the model system Caenorhabditis elegans that we affectionately call “worms” in the lab. Ambros and his colleague, Dr. Ruvkun, were curious about why certain mutant worms showed strange growth patterns. One mutant, lin-4, kept repeating early developmental events, while the other, lin-14, skipped these steps entirely.

The game-changing moment came when Ambros’ team, including Rosalind Lee and Rhonda Feinbaum, identified that the lin-4 gene didn’t produce a protein as expected. Instead, it made a small RNA that acted like a switch, controlling the expression of other genes, including lin-14. Initially, this mechanism was only observed in worms, but Dr. Ruvkun’s discovery of a similar RNA (called let-7) demonstrated that such small RNAs exist in many animals, including humans.

This discovery changed everything. It showed that small RNAs — now called microRNAs — regulate genes across species, opening up new avenues for research in disease diagnostics, treatments and genetic regulation.

What is your personal connection to Ambros, and how has working with him shaped your career?

I was a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Ambros’ lab at Dartmouth from 2001 to 2006. When I joined, only two microRNAs were known to exist in worms. I was excited to study these developmental timing genes. However, on essentially my first day, Dr. Ambros and his team submitted a paper that was published in the journal Science that revealed additional microRNAs in worms. This paper was published alongside the work from two other research labs, which together identified nearly 100 new microRNAs, not only in worms but also in flies and humans.

That discovery changed the direction of my research. I shifted my focus to study how these newly identified microRNAs regulate development, and this remains the core of my lab’s work at Marquette University today. Working with Dr. Ambros not only gave me invaluable research experience but also shaped my teaching and mentoring style. His curiosity-driven approach still inspires me.

Why is research on microRNAs important, and how does it impact human health?

MicroRNAs are essential for regulating development and physiology in animals. But their role doesn’t stop there. In many human diseases, including cancer, microRNAs are either overactive or not functioning properly. Some microRNAs act like “tumor suppressors,” preventing cancer, while others behave like “oncogenes,” promoting it. They can also serve as biomarkers for diagnosing diseases or predicting how they might progress.

microRNAs have become a focus for developing new treatments. Targeting these small RNAs could lead to therapies for cancer and other diseases. What started as a quirky discovery in worms has evolved into research that has practical applications in human health.

What value do teacher-scholars with strong research connections bring to Marquette?

Connections like mine with Dr. Ambros are invaluable, not just for me but for the entire Marquette community. I owe much of my career to his mentorship. Without his guidance, I might not have become a faculty member at Marquette.

One special moment was when Dr. Ambros visited Marquette to give a research seminar back in 2010 — long before he won the Nobel Prize. Our undergraduate and graduate students got a chance to meet with him over lunch and hear about his lab’s research. They can now brag that they ate lunch with a Nobel laureate! Over the years, he has provided feedback to my students at scientific conferences, which has been incredibly helpful for their growth. These connections make a lasting impact on both students and faculty.

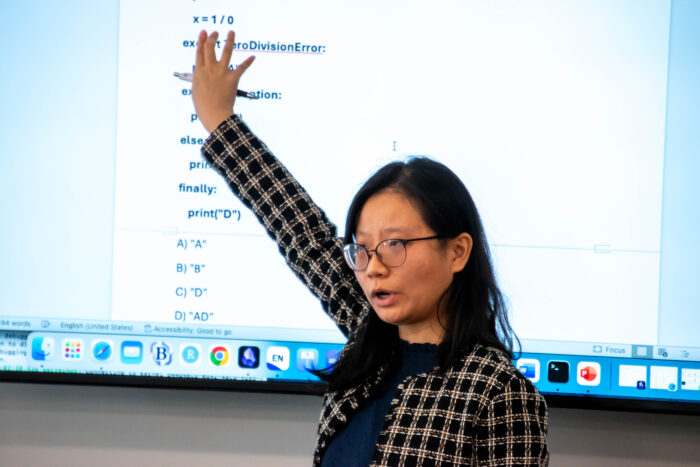

What advice do you have for students who want to pursue research in genetics or microRNAs?

My advice to students would be to follow your curiosity! There is so much we need to learn and so many unexpected findings just waiting to be discovered. I’m offering a one-credit seminar this spring where we will discuss the pioneering work that led to the discovery of microRNAs and the awarding of the Nobel Prize, along with current research in the functions of small RNAs. This class is open to sophomores, juniors and seniors and will focus on reading primary research papers, analyzing data and discussing different experimental approaches to study small RNA functions in model organisms. And if students are interested in working in the C. elegans model system, they can check out my lab or Dr. Lisa Petrella’s lab. Both are fun places to be engaged in undergraduate research!