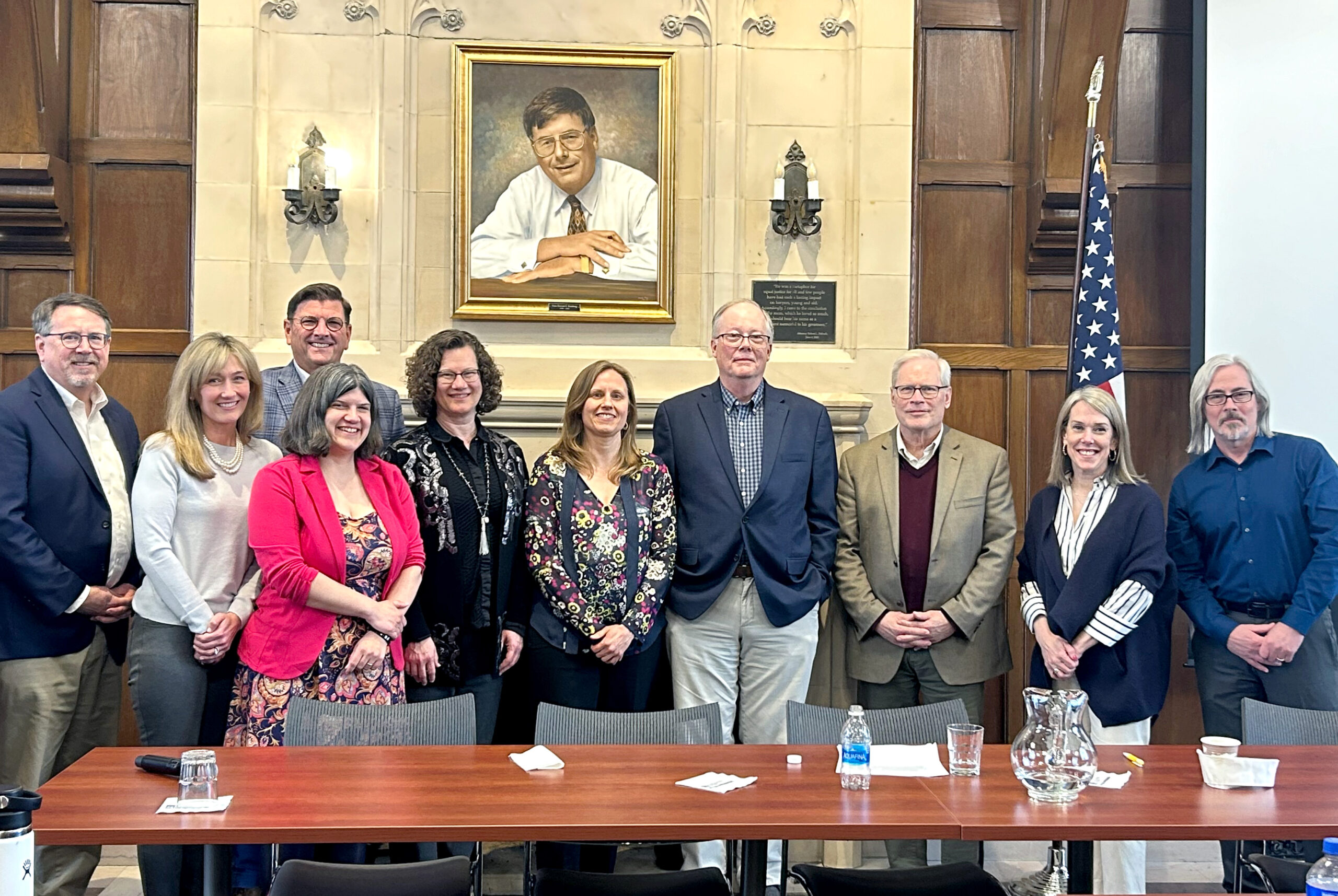

A distinguished group of historians of the Civil War-era United States gathered at Marquette on March 21 and 22 to honor the career of Professor Emeritus Dr. Jim Marten and reflect on the current state of their field.

Their presentations ranged from dogs’ utility in policing slavery and prisoners of war, to medicine and hygiene practices, to addiction and abolitionism — often drawing on Marten’s pioneering work on children and veterans that opened new approaches to research.

Over two stimulating days, these scholars raised questions about sources, temporality, and how our present directs new questions to the past while respecting its integrity. They engaged a robust audience of Marquette students and colleagues over issues of reenactment and commemoration, as well as what interdisciplinarity looks like in their field. There was additionally some gentle roasting of Marten, reflecting how conferences and professional networks shape genuine friendships.

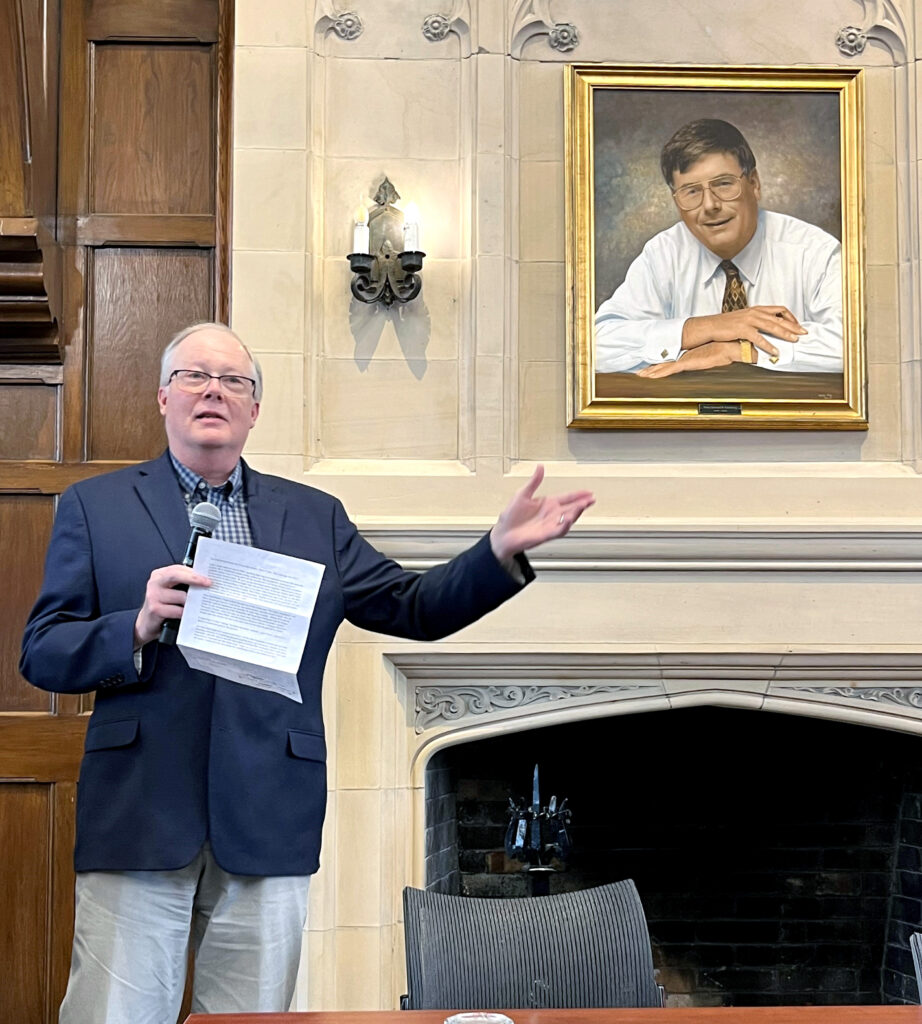

At the end of the symposium, Marten offered a few remarks underlining the importance of studying the past, especially in this current moment, which can be read below.

I can’t tell you how grateful and humbled I am by your words and presence. At times I felt a little disembodied, as though you were talking about someone else. Indeed, the way that you fit your work into mine, and suggested that I might somehow have had an influence on your own work, and the way you were able to explain to me — well, to the whole room — what I was trying to do in books I wrote 30 or 25 or 10 years ago was touching but also illuminating. And it reminded me of the importance of forming the kinds of relationships on display on this snow-globe Friday.

We get into this line of work for a lot of different reasons: a fascination with history, a love of explaining that history in our writing and in the classroom, connection with students, commitment to higher ed, the lifestyle. We could all name other reasons we’ve become historians. Along the way we find other moments to savor: that one student in the second row who gets your jokes, the smell of old paper in the archives, the time when a department meeting accomplished something meaningful.

I’ve been very lucky — perhaps more lucky than most. I landed a job at a good university with a serious group of historians in a city Linda and I have grown to love. The luck started when the person who was the search committee’s first choice for this job withdrew from consideration and I received my only invitation for an on-campus interview. And I spent a happy 36 years here, including 16 as department chair.

I think I can speak for a lot of the people here when I say that, once you’re in the field, you realize that the most important thing you get out of it is settling into a community of colleagues and friends. In your department, in your institution, in your field. And that’s why it’s so gratifying for us to be together here.

At a time when higher ed in general and history and the other humanities in particular are under dispiriting pressures, it is humbling and gratifying (but not to say unexpected, because we are a community, after all), that we can still come together to renew that community and to talk about things that are important and that matter to us.