Emma McGlynn, a freshman in the College of Nursing, was just weeks away from completing her first semester of classes. She has dreams of being a surgical nurse.

For a two-hour class period, though, Emma is a single parent of two: a 20-year-old daughter and a nine-year-old son. Emma works full time to support her family, but she hardly even has a spare second to visit the bank and cash the checks that keep them from losing their apartment.

“I had to resort to selling possessions, but we were robbed so that took away a lot of what I was planning to sell,” McGlynn says. “We resorted to selling appliances and furniture to pay for some emergency dental work that came up.”

Fortunately, McGlynn’s experience was only a role-play; specifically, it was part of the Missouri Community Action Network Poverty Simulation, an immersive exercise put on for the first time in the College of Nursing to educate students on what life below the poverty line is like.

For tens of thousands of Milwaukee residents, the choices portrayed in the simulation are real.

“This exercise is designed for students to gain greater understanding of what one month in poverty is like,” says Alicia Davis, clinical instructor in the College of Nursing. “We hope to provide insights on the kinds of things that community members may experience.”

Specifically, the simulation forces students to reckon with the hard choices imposed on individuals and families without enough resources to provide for the basics of life. With only enough money for food or medicine, which do you choose? What do you give up to afford the next month’s rent payment?

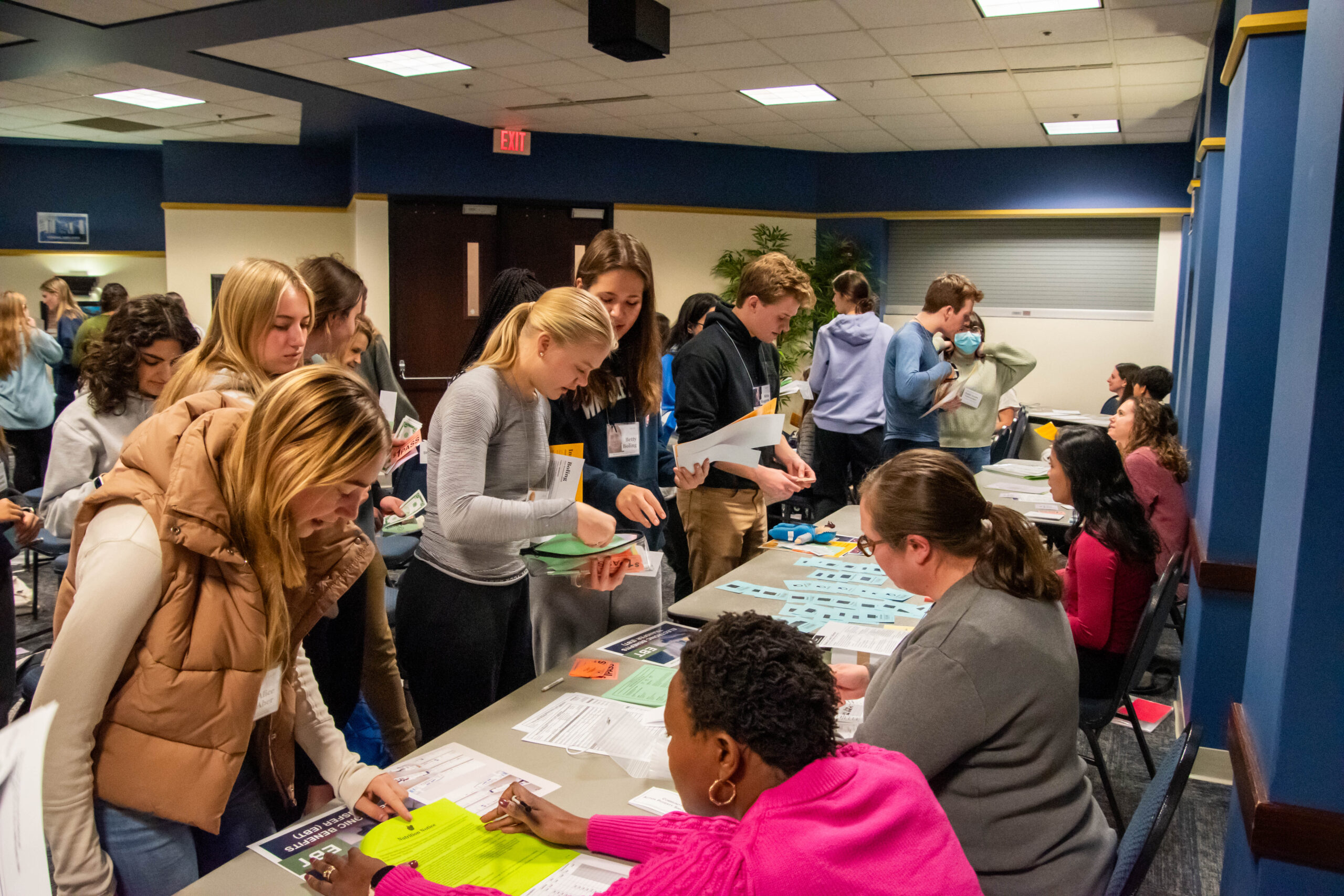

Students are assigned a random identity before the exercise begins with all the particulars of their new life: name, ethnicity/race, occupation, family status, available financial resources and any special circumstances, such as medical conditions. Volunteers behind folding tables line the sides of the room, with signs over each one’s head such as “quick cash” or “employer action network.” These represent the institutions that students might interact with, either of their own accord or under duress due to urgent needs.

Jenni Strait, clinical instructor in the College of Nursing, assumed the identity of a burglar who stole possessions from students when they were at work; an occurrence that can be devastating to people living in poverty.

“Part of my role was stealing from people and part of my role was inciting people in the simulation to engage in criminal activity of their own,” Strait says. “In the first two weeks, not many people took me up on the offer, but as we got into week three and week four and people got into desperate situations, I had students coming up to me and asking for those opportunities.”

Most in the simulation were enrolled in Nursing and Health in the Jesuit Tradition, the college’s introductory-level course. Participating in the simulation and writing a follow-up reflection is now a mandatory part of the class, which reflects the college’s prioritization of teaching social determinants of health.

“There are a lot of common illnesses that are influenced by or come directly from a patient’s social status,” Davis says. “If you have malnutrition, the treatment for that isn’t medicine; it’s food. Getting people the food they need and the housing they need is ultimately going to improve the health of individual patients and the entire community.”

Davis imagines a more expansive role in society for nurses, one in which they are advocates outside health care organizations in addition to being a health care worker within one. She mentions volunteering at a local food bank, starting a community garden and championing public health legislation as some of the essential actions nurses might take to create a more stable society and improve patient outcomes.

Making impoverished patients aware of available services is one of the paths of least resistance toward progress, a fact made clear from the results of the simulation. The students who ended the month in the best financial position were the ones who visited a volunteer with an unassuming sign above his head that read “community action network.”

At a group debrief afterward, students learned that the volunteer had ways to make their simulated lives easier, such as free bus passes and rent assistance. However, because students were only allowed to take a limited number of actions each week and couldn’t afford to miss a work shift, most of them passed up the opportunity.

This, too, is a realistic reflection of why government and nonprofit aid often doesn’t make it into the hands of those who most need it.

“The services people need are not always open when people need to get them,” Strait says. “As nurses, we need to be asking ourselves how our patients can find out what resources there are and how they can access them.

“Educating yourself on the resources in the communities you serve so you can give that information to your patients is important, as is getting involved and volunteering at a local level,” Davis says.

McGlynn is still more than a year away from her first clinical rotation in a hospital, but the exercise has her feeling more prepared than ever to connect with patients from every walk of life.

“I never viewed those less fortunate as lesser and I think it’s sad that some people might think that, but doing this simulation made me realize just how much some of our patients are coming to us in a really tight spot,” McGlynn says.