The yellow sheet of paper offers an easy-to-understand gateway into a complicated world for the ordinary renter. “Your landlord has started a court case to evict you,” it begins. Three short sections on the one-page sheet are labeled: Act. Get Informed. Get Help.

The fact that, since June 2023, the sheet is being offered to all tenants at the start of eviction proceedings in Milwaukee County Circuit Court is, in itself, a sign of significant changes in a complex issue—one that made Milwaukee the focus of national attention in 2016 but that presents itself across the country. Especially when it comes to “get informed” and “get help,” there have been substantial developments in Milwaukee County. In interviews, many who are involved in eviction matters, whether on the side of landlords or of tenants or working in the system itself, described the extent of initiatives aimed at increasing stability in housing while reducing evictions.

And lawyers are central to almost every facet of the changes.

Matthew Desmond’s 2016 book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, recipient of a Pulitzer Prize, focused almost entirely on Milwaukee. One of the book’s themes was the small percentage of people facing evictions, in a process many find baffling, who got any legal help.

Since then, eviction defense efforts in the region, primarily led by two longtime legal services organizations—Legal Action of Wisconsin and the Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee—have made representation by an attorney a reality for many more people facing eviction. Even so, lawyers are still involved in well under half of all cases.

Over the same period, other avenues of legal advice have grown in the region. Key developments include efforts offering free advice to tenants through Marquette Law School’s volunteer legal clinics; creation of an eviction diversion program, housed within the Milwaukee Justice Center in the Milwaukee County Courthouse and funded by a grant from the National Center for State Courts; and the rise of Mediate Wisconsin, a private nonprofit led by two Marquette Law School graduates who also have been adjunct professors at the Law School.

Avoiding eviction is only part of the growing legal involvement. Lawyers have increasingly become involved in working out the best feasible arrangements for both sides when tenants who are behind on payments are going to leave.

Lawyers also are at the forefront of one of the hottest issues involving evictions: whether the names of tenants in court actions should be made not easy to find in online records. That helps some people rent new apartments by making it harder for landlords to know a potential tenant’s full rental record.

Non-legal help also has grown. Agencies such as the Milwaukee Rental Housing Resource Center and Community Advocates have increased their work to assist people in finding places to live and staying in those places amid financial stresses. There was increased use of federally funded rental assistance grants during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, although much of that help has ended. The United Way of Greater Milwaukee and Waukesha County also has supported work to help people avoid eviction.

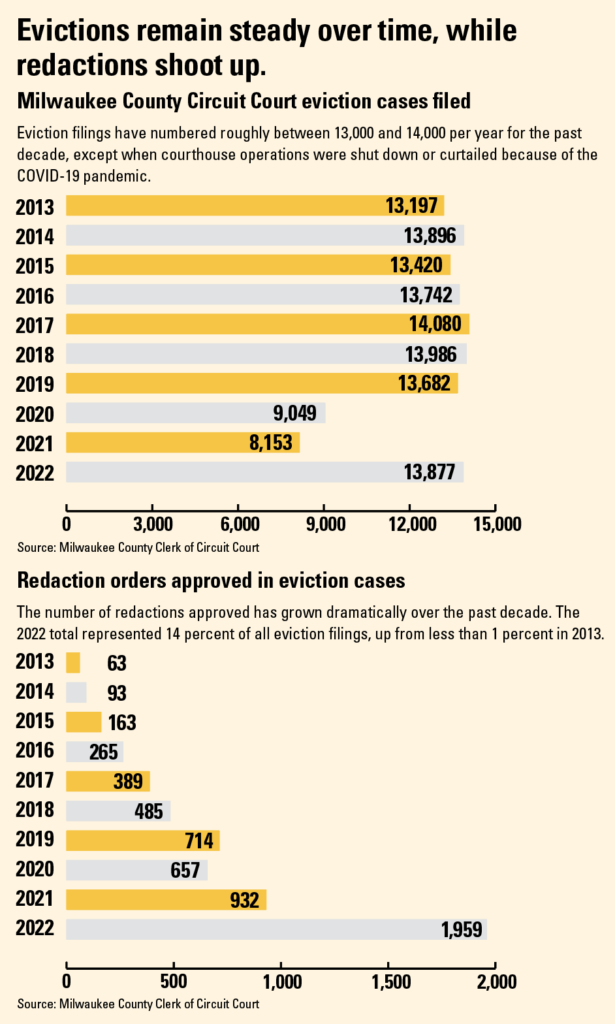

The pandemic and its spillover effects changed the eviction landscape. A nationwide moratorium was imposed on many evictions. Since the moratorium ended, the pace of evictions, while high, has not skyrocketed as some feared.

In all, the handling of eviction matters in Milwaukee County has changed, with legal representation and legal counseling as key aspects of that. Advocates generally say that the changes are good, but not enough, and critics generally say that the changes have brought improvements to the system, but with downsides.

A simple idea gets complex—and human

At a core level, an eviction is a simple legal matter. A tenant agrees through a lease to rent a place to live. If the tenant doesn’t pay, the property owner can go to court to get the tenant ordered to leave—can seek the remedy of eviction for the breach. In the longtime words of the Wisconsin Supreme Court (these being from 1979): “The decisions of this court have held that there are a very limited number of issues permissible in an eviction action.”

Yet eviction proceedings often become not only complex but intensely human. To observe cases in Milwaukee County’s small claims court is to glimpse a remarkable array of people and issues that they face in their daily lives.

On the owner’s side, the array ranges from corporate landlords with lawyers who know the system well to mom-and-pop landlords who may be as much in need of guidance on how to proceed as their tenants are. On the tenant’s side, the array often runs to low-income people who are struggling with major life issues while living in less attractive (though only somewhat “low rent”) places. The eviction process is both a symptom of their problems and a further cause.

It is instructive to look back at the way evictions were handled in court as recently as a decade ago. In Milwaukee County Circuit Court, the small claims division, which handles evictions, was based for years in a large courtroom on the fourth floor of the courthouse. The room often was filled with court employees, numerous lawyers, and even more numerous tenants. A range of “proceedings” were conducted simultaneously, involving everyone from the judge on the bench to parties huddling throughout the room, formal and informal conferences in rooms behind the courtroom, and conversations in the hallway outside, often involving people (including lawyers) on both sides of a case. To inexperienced observers, the scene was almost chaotic and certainly hard to grasp. “It was basically a huge cattle call, back in the day,” recalled one lawyer who represents property owners.

Raphael Ramos, L’08, was a staff attorney at Legal Action of Wisconsin before he was appointed earlier this year by Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers as a Milwaukee County Circuit Court judge. In an interview before his appointment, he described his work leading the nonprofit law firm’s Eviction Defense Project, launched in 2017. It is one of two legal assistance eviction-prevention programs in the county. The other, Eviction Free MKE, a three-year pilot project launched in 2021, is run by the Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee.

Ramos said that before the emergence of eviction legal assistance programs for tenants, a “justice imbalance” prevailed. He recalled how court proceedings often began with the questions: “Are you here for the eviction? How much do you owe?” Almost no tenants fighting an eviction were represented by an attorney. In contrast, landlords, generally more familiar with the process, were often represented by someone experienced in evictions.

Ramos recalled a story from several years ago that illustrated to him the stark difference legal representation could make. A Legal Action client agreed with his landlord to adjourn the eviction case while he obtained money he owed the landlord. The man didn’t think he needed an attorney for the next hearing and arrived unrepresented in court, ready to pay. But the landlord decided not to settle, and the eviction request was approved. The man later returned to Legal Action, but at that point, it was too late for anything to be done. The man broke into tears; his young daughter tried to comfort him.

“It was absolutely devastating,” Ramos said. “Preventing those sorts of situations is precisely why we have tried to increase access to representation. The harms people suffer because of eviction are not limited to displacement and economics; they are emotional, deeply personal, and change the way that people view the world. I have no doubt that the little girl and her father will remember that moment the rest of their lives, and it breaks my heart that they had to go through it, when it might have been avoided.”

“The need is significant, and the importance of attorney representation can’t be overstated,” Ramos said. “One of the most consistent themes that our tenant clients will tell us is that if they had a proceeding where they didn’t have a lawyer, the proceeding went fast, it was difficult to understand, and they barely, if at all, had the opportunity to speak.”

Ramos said, “We try very hard to make sure that the representation we provide leads to housing stability, not just a short-term fix. The work we do is not intended just to put a Band-Aid on things. . . . In doing that, there is an underlying benefit for the landlord as well, because if we can help mend the fractured relationship, the tenant has housing, the landlord has rent.”

Colleen Foley, executive director of the nonprofit Legal Aid Society of Milwaukee, said, “Where one side completely dominates and the court system is more focused on a gigantic docket that [judges] need to process, that’s not justice. The system’s not supposed to work like that.”

Attorneys representing property owners had mixed views of the changes in eviction work. On the one hand, several agreed that the increased number of tenants getting legal representation made proceedings fairer for tenants and leveled the playing field. Several said that dealing with tenants’ attorneys was often better than dealing with tenants directly because the attorneys understand the law and take a professional approach. That often helps lead to resolutions that are agreeable to both sides, within the circumstances.

But several property owners’ attorneys said that proceedings often are slower because more attorneys are involved and those attorneys use strategies for delaying outcomes. Some noted also that more property owners are calling on attorneys to represent them than in the past.

Several attorneys said that delays in concluding cases can mean increases in lost rent for owners, and extra costs for owners to pursue cases can mean higher rents or increased security-deposit requirements for all tenants, including those who pay their rent steadily.

Heiner Giese, a Milwaukee lawyer who has represented apartment owners for more than 40 years, said he has generally had good relationships with attorneys representing tenants. But he said, “Often, the most that attorneys for tenants can accomplish is to delay an eviction.”

Tristan Pettit is executive vice president of the law firm of Petrie + Pettit and head of the firm’s landlord–tenant team. He said that the substantial increase in the percentage of eviction cases involving lawyers for the tenants has slowed down many proceedings. But, he said, it has also had benefits. “If you have a difficult tenant, having an advocate [for the tenant] can make things much easier,” he said. He said that it took some time to adjust to changes, but the attorneys on his team generally have had helpful interactions with tenants’ attorneys. “Things are positive now,” he said.

A judge’s view on why attorneys add value

In general in Milwaukee County, the first hearing on an eviction case is conducted before a court commissioner. In the last several years, these have generally been done on Zoom, although in August 2023 that was phased out in most cases. If there are contested matters, the case then goes before a judge at a subsequent hearing in person.

Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Cynthia Davis, L’06, completed a year’s rotation in small claims court this past summer. So she has had a close-up view of how eviction proceedings are going. Her opinion on the increased role of attorneys representing tenants? “They truly add value to the process,” she said.

Davis gave four reasons for that conclusion:

(1) “Eviction laws are very technical,” she said. Some landlords who aren’t represented by attorneys make mistakes, such as giving the incorrect number of days to vacate premises. There can be 5-day, 14-day, or 28-day notices, with 5 days the most common. Lawyers can spot flaws in notices and in how a notice is served, she said.

(2)There are sometimes valid defenses against an eviction, such as that the landlord is retaliating against a tenant or the landlord has not fixed a condition that is covered by “rent abatement” rules. In general, an attorney articulates a defense against eviction better than an unrepresented tenant does. Retaliation defenses rarely succeed because they are hard to prove, she said, but they need to be considered where raised.

(3)Even if there is no defense at law in an eviction action, a lawyer often helps negotiate a stipulated dismissal, either a payment plan or an agreement to leave, or a combination of the two. Reaching agreement on such things is often in the best of interest of both the landlord and the tenant.

(4)Lawyers know how to make requests for redaction or sealing of a record involving eviction, which can help their clients in the future as they seek other housing.

Some do not favor all the changes. That includes those landlords and their advocates who question all the public and philanthropic support going to provide attorneys for tenants. Yet some advocates focused on improving the general housing picture for low-income people also fall into this group. In the Stanford Law Review Online in July, two law professors questioned giving legal representation of tenants priority over what they regarded as the bigger need of tenants: rent money.

Juliet M. Brodie, a professor of law at Stanford Law School, and Larisa G. Bowman, a visiting associate professor of law at the University of Iowa College of Law, both have extensive experience representing low-income families facing eviction.

Here’s their view, as summarized by the law review: “Most low-income tenants facing eviction do not need a lawyer. They need rent money. . . . If we want to reduce evictions, tenant lawyers are not the best tool. Rental assistance could resolve, or even avoid the filing of, most eviction cases.” The authors said that the $46 billion in federal funds made available during the height of the COVID pandemic to help people who otherwise would have been facing eviction showed how much increased rental aid could reduce eviction problems. They called the movement to provide every tenant a lawyer in eviction proceedings “misguided.”

Evaluating the legal assistance programs

Both eviction legal assistance programs involved in Milwaukee have been evaluated by outside organizations.

The first 16 months of work by Legal Aid’s Eviction Free MKE—September 2021 through December 2022—were studied in a March 2023 report done for the United Way of Greater Milwaukee

and Waukesha County by Stout Risius Ross, a Chicago-based consulting firm. According to the report:

- Through the first half of 2021, 2 to 3 percent of tenants had legal representation in eviction cases; from July to November 2022, the monthly rate rose to 14–16 percent.

- Eviction filings rose in 2022 to more than 13,850, a 70 percent increase from 2021, when court operations were slowed by the pandemic and (for part of that earlier year) a federal moratorium on evictions was in effect.

- During the period studied from September 2021 through 2022, 58 percent of eviction cases were dismissed when both parties were represented, compared to 46 percent when only the landlord was represented.

- Similarly, during the same 16 months, when only the property owner was represented, 38 percent of cases resulted in a default judgment, with the tenant failing to appear in court. When both parties were represented, the default rate was 29 percent.

Milwaukee County likely received economic benefits worth $9 million during the 16 months as a result of Eviction Free MKE. The estimate covered money that did not have to be spent on social services and foster care and money saved by reducing the number of people who leave Milwaukee County, among other things.

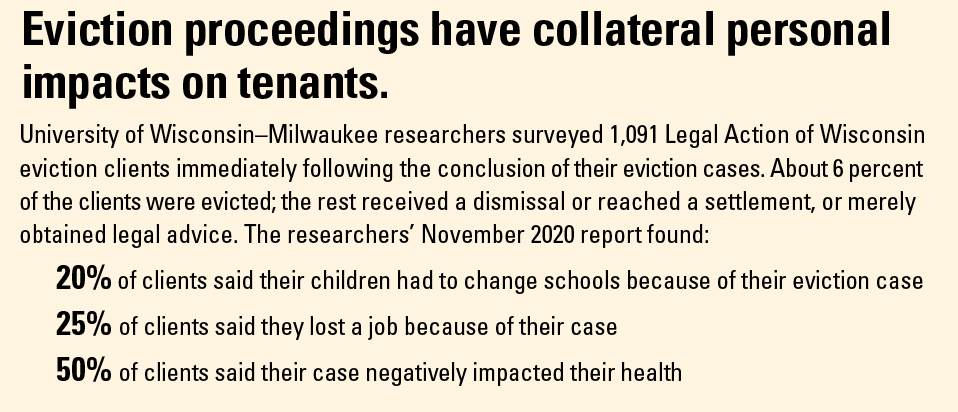

The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s 2020 survey of Legal Action of Wisconsin’s clients found:

- 79 percent of clients who got their case dismissed or reached a settlement agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “I would not have been treated as fairly in court without the eviction defense attorney.”

- 92 percent of clients whose cases were dismissed or settled agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, “Having an attorney changed the outcome of my case.”

- 90 percent of clients—including clients who were evicted—agreed or strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the outcome of their case.

A day in eviction court

Some vignettes from contested eviction cases on a typical day before Judge Cynthia Davis during her tenure presiding in Milwaukee’s small claims court may be instructive:

- Davis accepted a stipulated dismissal, under which a 29-year-old tenant agreed to move out. Only Legal Aid attorney Mitchell Yurkowitz, representing the tenant, appeared in court. He requested and was given an adjournment to file a motion seeking to redact his client’s name from the public record (Davis granted the motion at a hearing three weeks later).

Seven months before that action was filed, a different landlord had sought an eviction against the same individual. The landlord in the earlier case was represented by an attorney, but the tenant was not and did not appear for the hearings. The landlord secured a judgment of eviction and for $6,467 for damages to the premises; the latter had not been satisfied as of early June. There was no redaction in that case.

- A second vignette, involving different parties: At a court proceeding three months before the eviction hearing, the tenant had appeared by phone, and the attorneys for both parties appeared by video over Zoom. At the subsequent eviction hearing, only Yurkowitz, the lawyer for this defendant also, appeared in person. Davis granted a stipulated dismissal, with the landlord dropping money claims.

- A third: A suburban Milwaukee limited liability corporation (LLC) filed for an eviction of a woman and her mother, who were both assisted in court by a Mandarin Chinese interpreter. The LLC landlord appeared in court without an attorney, and the woman was represented by a Legal Aid attorney, who was able to get the first eviction hearing adjourned while working toward an agreement. A stipulated dismissal was sought, but at an eviction hearing later, the landlord, appearing in court along with the tenant and her lawyer, said he no longer agreed to the stipulation.

At that second hearing, Legal Aid attorney Gilbert Malis, L’19, asked Davis to accept the stipulation because the nonprofit organization, Community Advocates, had paid the landlord $4,950 in rent owed. Davis agreed and dismissed the case. Davis also granted Malis’s motion to redact the defendant’s name. Citing a balancing test under the law, she said the case had “limited public interest,” whereas a publicly searchable record of the tenant’s name in the caption of the case could hurt the tenant’s ability to rent in the future.

- Vignette four: Another suburban Milwaukee LLC sought an eviction against a 26-year-old woman. At the eviction hearing, the tenant and her attorney, Jesse Owens, appeared in person, as did a member of the LLC. Owens persuaded Davis to dismiss the case, arguing that the LLC did not have authority to sue because it was not registered at the appropriate time with the state; Davis rejected the plaintiff’s argument that the LLC had registered two weeks before the hearing and that the registration could be retroactive. Davis also granted Owens’s redaction motion, citing the balancing test.

The LLC filed a new eviction action against the woman. Four months later, that case was still pending. Two eviction cases had been previously filed against her, in 2018 and 2020.

- And a fifth story: Davis approved a stipulated dismissal, under which a 42-year-old tenant agreed to pay the landlord $800 and move out within a few weeks. Both parties were represented in court. In moving for redaction of the defendant’s name, the tenant’s lawyer, Legal Action’s Jill Kastner, said that her client needed to rent a new apartment and that she had seen “for rent” notices saying applicants cannot have been evicted. The motion was not opposed, and Davis granted it.

Eviction actions were also filed against the woman in 2012, 2015, and 2019. She was not represented in those cases, and no requests to redact were made.

To be sure, any sample of vignettes will be incomplete. In particular, Davis entered any number of eviction judgments, even on the day discussed.

The controversy over redacting records

As the foregoing vignettes may suggest, perhaps the hottest issue in eviction work currently is “sealing” or, somewhat more accurately, “redacting,” which results in the name of the tenant being not searchable in the case caption in Wisconsin’s online database of court proceedings, known as CCAP. From a tenant’s perspective, the most valuable work of attorneys representing tenants is often their success in obtaining a ruling to redact.

The number of requests in Milwaukee County Circuit Court to redact names of defendants in eviction filings has skyrocketed. In 2011, according to the clerk of the court, there were 63 such requests. In 2022, there were 1,959. “These have flooded our system,” Davis said. She was spending two mornings a week on such requests while she was on the small claims bench.

The heart of the issue, on the tenant’s side, is the impact of having a name on a public record. One of the routine steps that landlords take when considering an application to rent is to see if the potential tenant has been involved in an eviction proceeding, even in cases that didn’t result in an eviction order. Having such a record is very likely to be a barrier for someone looking to find a new place to rent.

Requests to redact a name typically are not granted when an eviction proceeding reaches a final judgment of eviction. But a large number of eviction filings do not end up with final judgments because cases are dropped or dismissed, whether pursuant to a formal agreement or otherwise.

And the filing of the case in itself creates a public record. Generally, Wisconsin law strongly favors—indeed, requires—the accessibility of public records. Among other provisions, the legislature has provided (Wis. Stat. § 19.31) that “[t]he denial of public access generally is contrary to the public interest, and only in an exceptional case may access be denied.” Numerous cases have been decided to guide a judge’s discretion in this context.

Not surprisingly, there are differing views on when or even whether to redact records in the eviction context, with property owners generally on one side and advocates for renters on the other.

Tim Ballering heads Affordable Rental Associates, which owns 300 units generally on Milwaukee’s south side. The company also manages another 350 units. Ballering said that new tenants who have had an eviction in the prior year fail to fulfill their lease obligations (to pay their rent) at significantly higher rates than other new tenants. By three years post-eviction, the track record is about the same as that of tenants without eviction records. Preventing landlords from seeing names of people who have been evicted is not only a problem for landlords, he said, but also for people who are better candidates to be reliable renters yet who may lose out in getting an apartment to someone with a past eviction.

Nick Toman, L’08, managing attorney at Legal Aid, had a different point of view. “You have to have a little bit of faith in the justice system and the courts and the judge to make that determination—that the merits of the eviction aren’t relevant to the future rental prospects,” he said. “That’s what the courts are saying when they grant the motion to seal, that this eviction doesn’t fairly reflect on this person as a tenant and future landlords shouldn’t rely on the existence of this eviction to make determinations about them.”

Toman said that some landlords read too much into someone’s contesting an eviction proceeding. “They’re not only going to assume that you deserved to be evicted, but they’re going to assume that you’re a pain in the butt and you fought it,” he said.

Francesca Voci, L’22, an attorney on the evictions team at Legal Aid, said she understood the landlords’ views, but that not all people who became involved in evictions are poor candidates for future rentals. Some went through difficult circumstances such as medical problems or job loss and are ready to move on. Difficulty finding a place to live can make that harder. Voci regards housing as “a human right,” and allowing people to have stable shelter is often a key to stabilizing their lives, she said.

One attorney for property owners who asked that his name not be used said he felt public records laws were being manipulated by lawyers for tenants. Court records generally are expected to remain public, he said. “Nobody is there advocating for the public,” he said. He understood why individual tenants want their names kept off the record, but in the broader picture, in his estimation, it’s in the public interest to keep records open.

Milwaukee attorney James Bottoni, L’00, who represents landlords and management companies, had a different view from some other attorneys representing property owners. He said he usually doesn’t take a position on redacting tenants’ names in eviction proceedings. He said he tells tenants that it is in their self-interest to leave an apartment before an eviction judgment is filed. If they leave and don’t owe the owner money, his client’s interest in their cases is over.

When she was presiding in small claims court, Davis said, she generally ruled for redacting names in cases that were resolved short of an eviction order. She said she weighed the interests, as required by law, and often found them to weigh in favor of making a tenant’s name not publicly searchable. But, she said, with the rapidly increasing number of requests to redact names in CCAP, consistent policy is needed, which might require action at the state level.

More recently, at an administrative rules meeting on October 9, 2023, Wisconsin Supreme Court justices voted 4 to 3 to have a court commissioner draft a proposed order to reduce how long records of certain eviction proceedings are to be kept on the CCAP website.

The rise of mediation

In the aftermath of the publication of Evicted, the Matthew Desmond book that drew national attention to the phenomenon of evictions in Milwaukee, judicial, political, and civic leaders launched initiatives to reduce the number of evictions and help tenants keep or find stable housing. Providing legal help to those served with eviction papers was only one goal. Avoiding eviction actions in the first place by resolving landlord-tenant disputes before they reach the court system was more appealing from all points of views.

Mediate Wisconsin was created in 2012 as a nonprofit, grant-funded organization focused on reducing home foreclosures by working with owners and lenders to find paths beneficial to both. The effort was, in part, an outgrowth of work through Marquette Law School to respond to what was then a home-foreclosure crisis.

In 2017, Mediate Wisconsin, led by Amy Koltz, L’03, along with Joanne Lipo Zovic, L’99, began offering mediation services related to eviction cases or situations that are headed toward the court system. Koltz said, “We found that landlords and tenants who want to engage in mediation are looking for a solution and haven’t been able to reach agreement. Often we find that it is challenging for them to communicate effectively” because one party or both may be avoiding the other. “When a third-party mediator engages in the conversation, communication can be more productive many times,” she said, and that can lead to agreement on a payment plan or a plan for the tenant to leave without court action.

Property owner Tim Ballering said, “Mediate first is a concept that we were unaware of in our industry.” The impact of COVID-19 accelerated efforts to mediate, he said. “A lot of people knew mediation was available mid-process, but to do it upstream is best for everyone.” He said mediation efforts overall have been “very successful.”

Koltz said that Mediate Wisconsin can sometimes help tenants find financial help with paying rent or take other steps to resolve problems. The mediators collaborate with the legal service programs for tenants, as well as with the Milwaukee Rental Housing Resource Center, a collaborative effort of nonprofit and government groups aimed at helping both tenants and landlords with housing issues.

With a two-year grant from the National Center for State Courts in 2022, Milwaukee became one of 12 places in the United States with an additional tool for preventing situations from becoming eviction proceedings. Meagan Winn became the coordinator for the Eviction Diversion Initiative, which is housed in the Milwaukee Justice Center offices in the Milwaukee County Courthouse.

Winn is not a lawyer and is not a mediator. But, receiving referrals from courts, agencies, and others (including walk-in traffic), she tries to direct people to places where they can receive help. “My goal is to have people get to the right place as quickly as possible,” Winn said. The definition of diversion is flexible, she said. She aims to prevent avoidable evictions through such possibilities as emergency assistance and mediation. She characterized the work as trying to take “a problem-solving approach.”

Is making attorneys available to more people facing evictions helpful? Winn said case filings have stayed about the same, but eviction judgments have gone down, which suggests to her that the answer is “Yes.” But the bigger issue is the shortage of affordable housing in Milwaukee while so many people are living in poverty, she said.

In addition to the mediation efforts, there is the informal but often-effective avenue for working out settlements: conversation and negotiations between attorneys for the parties, whether in a courthouse hallway, as has often happened, or elsewhere.

Ramos, while a Legal Action leader on eviction defense, said that more than 90 percent of eviction cases handled by Legal Action result in evictions being avoided or delayed. Postponement has value for clients, he said, because it gives them time to plan for a move, rather than being forced out after a rushed, humiliating visit from sheriff’s deputies. And settlements negotiated by attorneys are higher quality than what tenants can typically work out on their own, he said, given that they build in protections such as more time to pay back rent or to move out if that is what is agreed upon.

Lawyers also can help in cases that are more cut and dried. When it’s not disputed that a tenant owes back rent, an attorney often can quickly arrange to get a landlord paid through programs run by nonprofits such as Community Advocates. Attorneys, while advocates for their clients, also bring a professional approach to the situation and are able more calmly to find resolutions than perhaps a tenant and landlord could on their own, said Legal Action’s Toman. “Half my job is to be like the Vulcan” character in Star Trek programs, he said: “to give dispassionate, logical analysis.” “Sometimes that means the landlord is not going to be punished in the way the tenant thinks the landlord should be punished, but that’s not going to help them and their family find stable housing. It gets real emotional real fast when you’re dealing with your home and your family and all of your possessions.”

Some lawyers who represent landlords say that the balance in eviction proceedings has moved too far toward helping tenants. One attorney expressed a fear that that the system is becoming “a court of law for landlords and a court of equity for tenants.” If anything is wrong on the landlord’s side, a case will be dismissed, but tenants don’t get held to the same standard, he said.

In any event, with the end of the surge of pandemic-related funding that slowed evictions and made more rent assistance available, and with high levels of political gridlock at the federal level and in many statehouses, expanded initiatives related to tenants seem unlikely.

Asked what he sees ahead, property-owner Ballering said, “I don’t know if I see much changing. What would I like to see? More getting in front of the case before proceeding, more mediation, more help for people.”

With the increased participation of lawyers, progress has been made in representing tenants and seeking ways to avoid evictions and, for some, in stabilizing housing. But the problems are far from solved, for reasons that go well beyond small claims court.