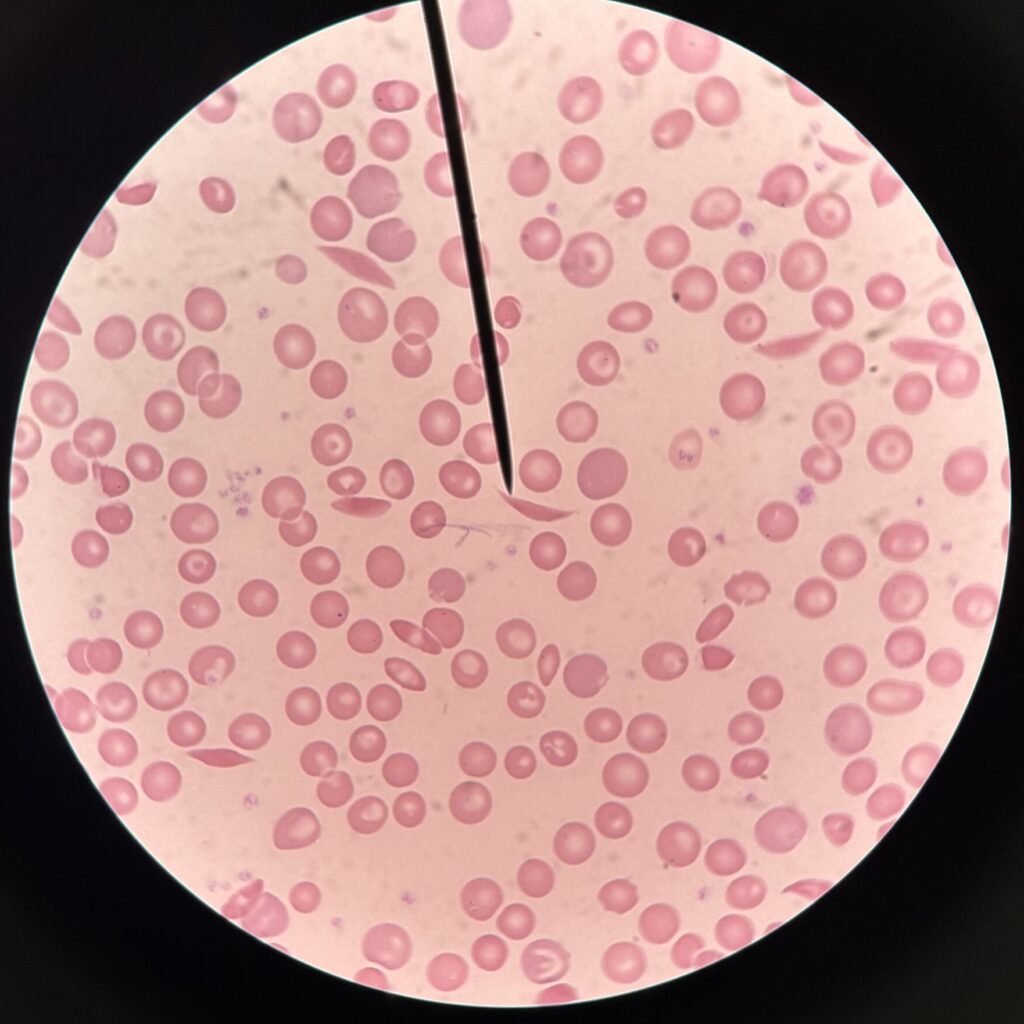

One in 100,000 Americans lives with Sickle Cell Disease, a genetic blood disease that causes red blood cells to become deformed, changing from their typical round, smooth structure to a sickle-shaped and sticky configuration. Those with the disease typically experience fatigue and pain localized to joints or areas containing small blood vessels.

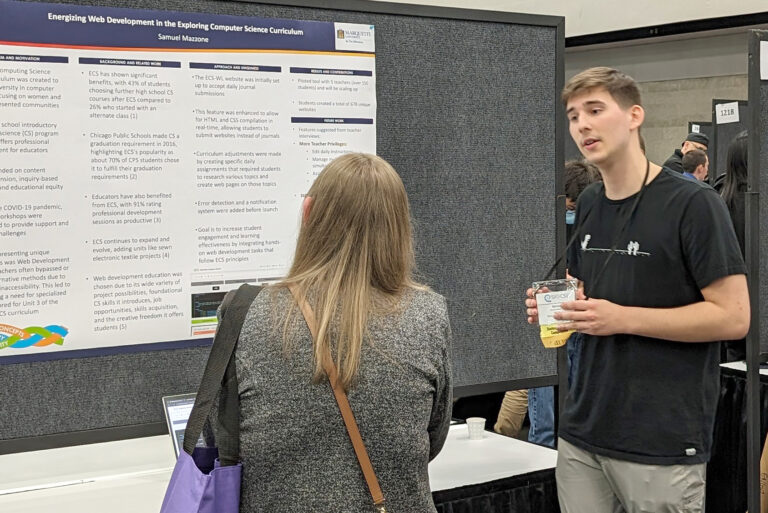

Early screening can hold the key to mitigating symptoms and to better understanding how to successfully treat the condition. In the Medical Laboratory Science Department in the College of Health Sciences, students are learning how to identify the disease in Dr. Valerie Everard-Gigot’s hematology course.

“Sickle Cell Disease is one of many hematological issues that is diagnosed with the aid of a medical laboratory scientist,” Everard-Gigot says. “The blood provides many remarkable clues, and visual examination of blood from an individual with this disease can inform clinicians about the degree of sickling and the extent to which the body is responding by producing new red blood cells.”

Medical laboratory scientists are a critical piece of the diagnostic procedure in all forms of Sickle Cell Disease, helping provide patients with needed answers.

What causes Sickle Cell Disease?

Sickle Cell Disease is an inherited condition that results in the production of abnormal hemoglobin – the protein responsible for imparting the red coloration to a red blood cell and for the oxygen carrying capacity of the cell.

Sickle Cell Anemia is caused by a mutation in a gene encoding the “globin” component of hemoglobin. The resultant single amino acid mutation, in turn, results in the synthesis of abnormal protein globin chains – the mutated hemoglobin with the altered protein change is known as “Hemoglobin S”

“When red blood cells form into the sickle shape — hemoglobin S — they have a harder time freely flowing through vessels and subsequently cause ‘roadblocks’ to healthy red blood cells,” Everard-Gigot says. “The healthy red blood cells will attempt to move past the roadblock of sickled cells, but as they attempt to do so, their cell walls or membranes become compressed and pulled. This can result in elongated cells that become stressed and eventually destroyed, producing a reduction in available healthy red cells and a diminished oxygen carrying capacity in the body- the ‘anemia’ part of sickle cell anemia.”

With less oxygen being delivered to tissues, in addition to fatigue, pain can be a common symptom of Sickle Cell Disease, though the precise mechanism of pain induction is not completely understood, Everard-Gigot says.

In addition to Sickle Cell Disease in which an affected individual inherits a copy of the abnormal hemoglobin S gene from each gene (or HbSS), it is possible to inherit a different abnormal form of hemoglobin from one parent, and thereby produce one of several variants of the condition, some of which produce milder forms of the disease. Also, in some individuals who inherit only one copy of an abnormal hemoglobin gene, symptoms of fatigue can occur with strenuous exertion or dehydration. Such individuals, while are ‘carriers’ of disease, are said to have the sickle cell trait.

Medical laboratory scientists ensure the accuracy and fidelity of this test and of many critical laboratory tests by mastering extremely technical diagnostic instruments for optimal sensitivity and specificity. This commitment to accuracy prevents errors that could be incredibly harmful to human health.

To learn more, visit the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America website.