Exercise science faculty members Dr. Sandra Hunter and Dr. Christopher Sundberg have received a $3 million NIH R01 award to study fatigue in prediabetes patients. A clinical trial will examine the potential for a special exercise regimen to reverse the fatigue and help patients manage prediabetes in order to prevent it from progressing to Type 2 diabetes.

Although adding more exercise to daily routines is often one of the first suggestions doctors make when diagnosing a patient with prediabetes, exercise physiologists now know of a complicating factor. Prediabetes, the elevated blood glucose condition affecting roughly 38 percent of Americans, can itself make exercise more difficult by creating muscle fatigue.

A major new clinical trial led by Dr. Sandra Hunter, professor of exercise science, and Dr. Christopher Sundberg, assistant professor of exercise science, addresses this issue head on, investigating exercise interventions that may protect against prediabetes muscle fatigue and, in turn, help patients better manage their condition with exercise. A $3 million R01 award from the National Institutes of Health will fund the five-year project and enable the team to examine how strength training and blood-flow restriction training can improve prediabetes fatigue. If this approach works, it could improve the daily lives of prediabetic patients and help prevent the condition from developing into Type 2 diabetes, Hunter says.

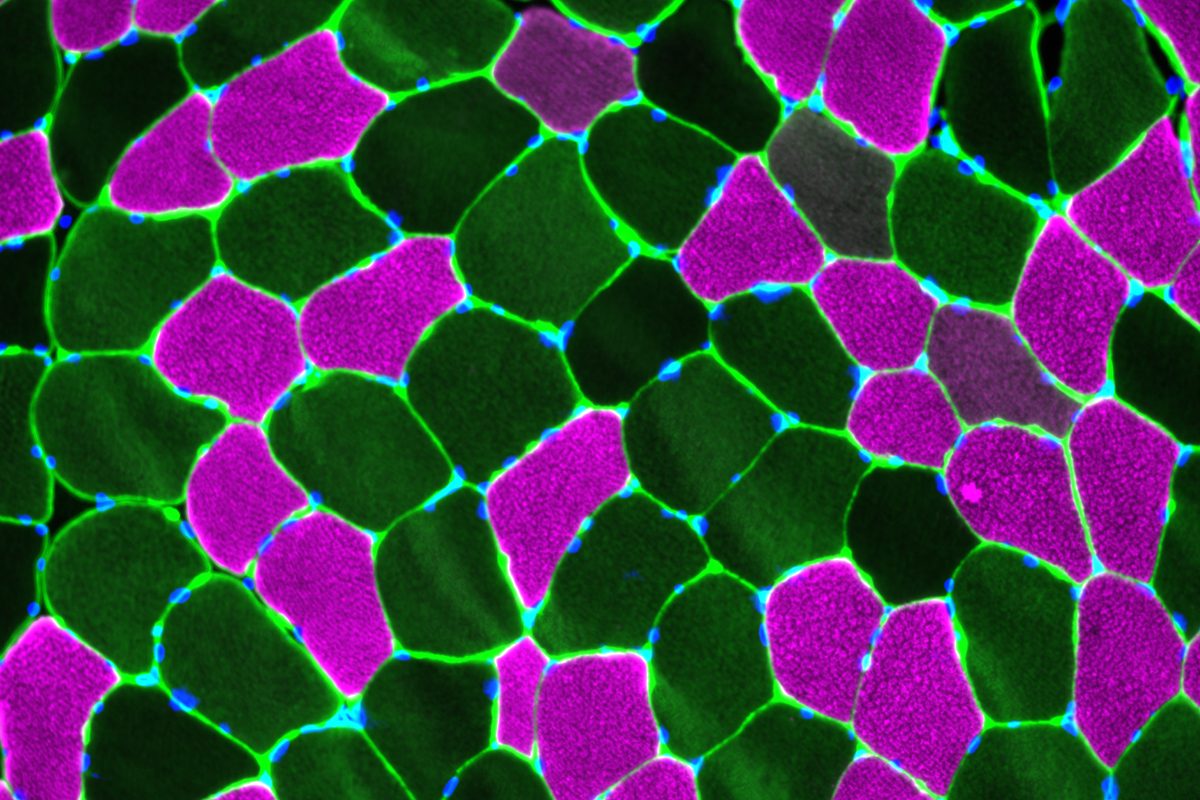

Despite its prevalence, prediabetes is still relatively understudied. Previous research conducted in Hunter’s lab identified skeletal muscle as a primary contributor to prediabetic patients’ fatigue. In their new work, Hunter, Sundberg and colleagues will investigate whether inadequate blood flow and oxygen delivery to a person’s muscles is contributing to this fatigue.

They will also study whether strength training, which promotes blood flow to the exercising muscles, and blood-flow restricted exercise, which uses an external pressure cuff to increase strength gained using lower resistance loads, can improve blood flow and muscle metabolism in prediabetic patients. Restricting blood flow during exercise may seem like a paradoxical treatment for patients with already insufficient blood flow, Sundberg acknowledges, but it may help prediabetic and diabetic patients receive greater strength and endurance gains from less physically challenging workouts. “In young, healthy people, exercise coupled with blood flow restriction is thought to help increase muscle mass, strength and endurance, and is currently used in clinics. Our study will determine its effectiveness in people with prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes,” he explains.

By joining their teams, Hunter and Sundberg will combine their expertise and be able to thoroughly assess the potential causes of fatigue in patients with prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes and how these patients respond to this new exercise regime. The Hunter lab will focus on the potential changes in the nervous system and the large vessels delivering blood to the muscles, while the Sundberg lab will use an MRI scanner to look at the structure of the muscle and the metabolism occurring during exercise. They will then take biopsy samples from the muscle to see how the individual muscle cells and small blood vessels change in response to the exercise training. “There is some evidence from healthy, young people that exercise with blood flow restriction increases the expression of genes for improving the function and growth of small blood vessels in the muscle. Our biopsy studies will determine what happens to the small blood vessels and muscle cells in people with prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes,” Sundberg explains.

With these potential improvements, researchers hope that prediabetic patients will have an easier time managing the condition through exercise. “Prediabetes can be reversed with a change of exercise habits and diet, but Type 2 diabetes is much more difficult to reverse — if not impossible,” Hunter says. “Identifying the causes of muscle fatigability and interventions to stop or slow the potential progression from prediabetes to Type 2 diabetes are important steps to increasing the health, quality of life and life expectancy for these individuals.”

Adults 40-70 with prediabetes, diabetes and healthy blood pressure are encouraged to participate in this study of muscle fatigue (compensation provided). Contact 414-288-1631 or hunterlab@marquette.edu.