A Marquette scholar’s fellowship at an influential Chicago library brings life to the cultural history of deafness.

Eighteenth-century Europe was a time of renaissance and revolution. It was the heyday of the Enlightenment, when philosophers and intellectuals embraced new ideas about morality, individualism, science and progress.

Even today, Enlightenment-era ideas stick around in our institutions — they influenced the development of modern medicine and democratic governments, for example. They also spurred modern concepts about gender, sexuality, race/racism and disability. “When I read about the social worlds depicted in 18th-century literature, they feel somewhat familiar to our own time, but in other ways they feel so distant,” says Dr. Jason Farr, associate professor of English.

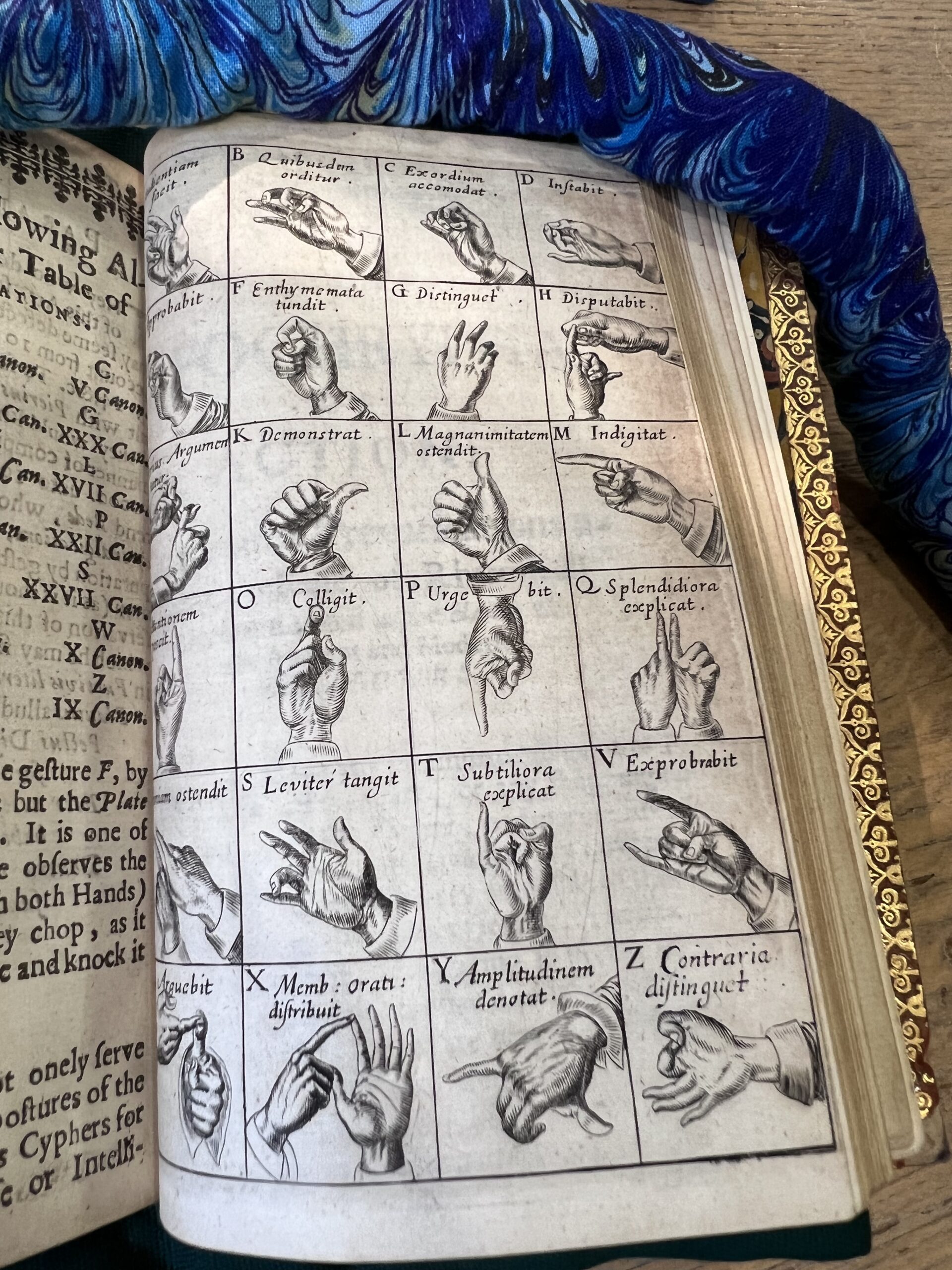

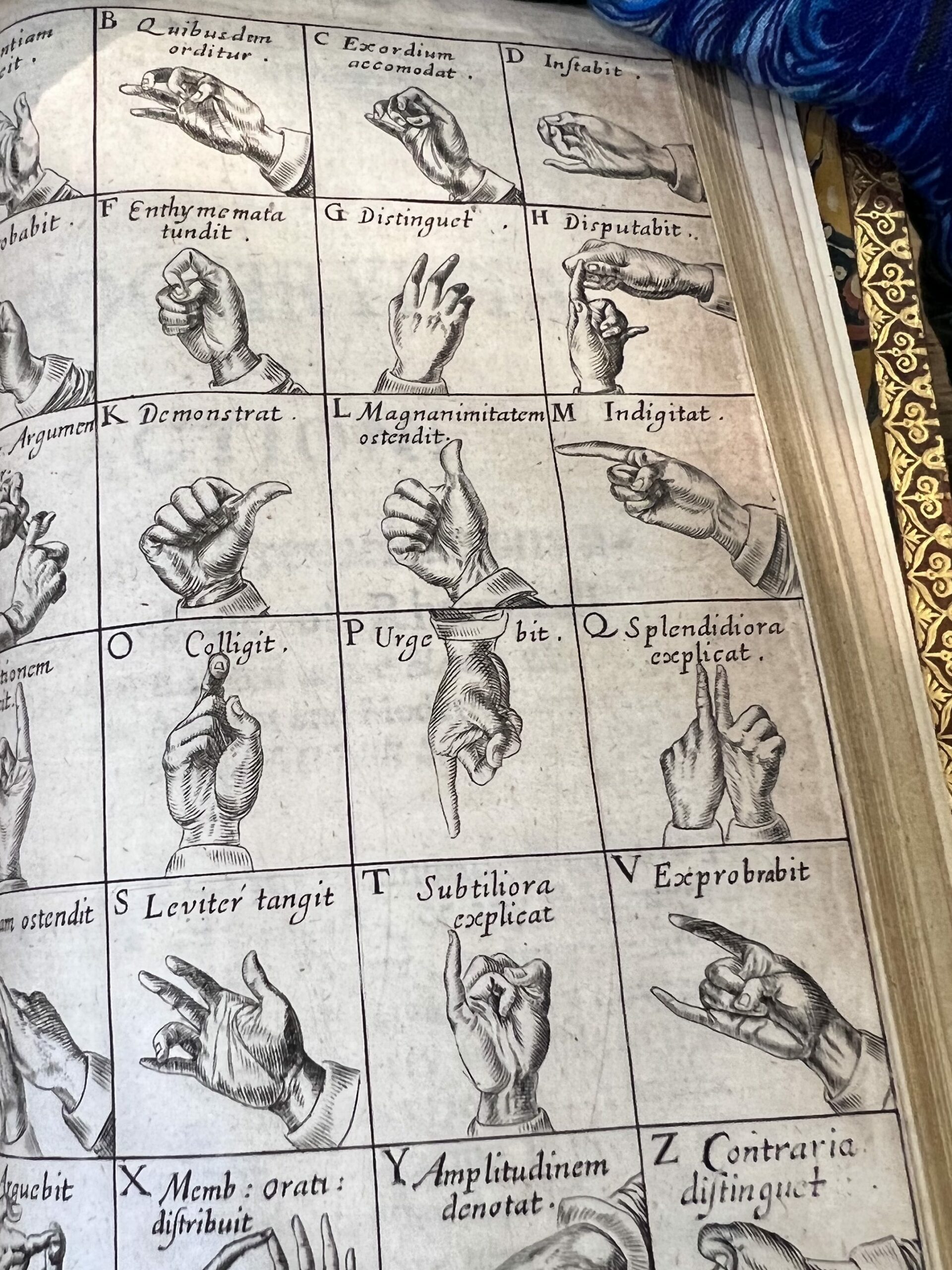

Farr’s research focus on the portrayal of disabled individuals in Enlightenment-era literature earned him a prestigious residential fellowship at the Newberry’s Center for Renaissance Studies to research his second book, Deaf Resonances: Deafness, Sound, and Multimodal Communication in Eighteenth-Century Literature.

Farr says the project came about after researching a chapter for his first book, Novel Bodies: Disability and Sexuality in Eighteenth-Century British Literature. In the 1720s, several novels and stories were published about a deaf man named Duncan Campbell who was a soothsayer. “After researching the cultural, linguistic and medical contexts of deafness for this chapter, I realized that there was so much more to be said,” Farr explains.

Enlightenment-era society largely held ableist views about deaf or disabled people, Farr says. But these portrayals vary widely. In some novels, deaf characters are depicted as heroic or having supernatural abilities. There are instances of physically disabled women running estates without the help of men and having intimate relationships with other disabled women.

“Not all 18th-century literature is subversive, of course, and much of it reinforces dominant ideas about disability,” Farr says. “But there’s also great complexity and nuance.”

Being able to study at the Newberry gave Farr access to an extensive collection of 18th-century writing about deafness, including treatises about some of the earliest mentions of formal education for the deaf. “It was an absolute dream,” he says. “To have the time and space to focus entirely on my research is an extraordinary thing, and I didn’t take it for granted.”

The Newberry, located in Chicago and renowned for its collections in history, religion, arts and culture, has been a research hub for dozens of Marquette scholars since the 1980s. Dr. Albert Rivero, the Louise Edna Goeden Professor of English, was the recipient of a Newberry fellowship back in 1984 that helped him finish his first book. Today, he is one of Marquette’s representatives for the Newberry Center for Renaissance Studies Consortium, which provides access to grants, workshops and seminars.

“It’s only a handful of schools that are members of a consortium like this,” Rivero says. Not only does membership boost access to timeless resources for students and professors, it also denotes Marquette’s status as a serious player in the field of Renaissance studies.